#9: The Power of Agglomeration | Public but Gated | Transaction Costs in Cities | Governing City-Regions

An essay on the importance of agglomeration in urban planning, an insight on the impact of gated streets, an explanation of transaction costs, and a book recommendation on governing city-regions.

Essay

The Power of Agglomeration

Author: Bimal Patel

The Delhi Master Plan 1962 was India’s first statutory ‘Master Plan’ for a city. It was held up as an exemplar by the union government and all states were encouraged to emulate it. Along with this the union government also promoted a Model Town Planning Act and provided funds from the Third Five Year Plan. As a result, over the next two decades, master planning became firmly institutionalised across India.

But master planning never worked. Delhi’s 1962 plan, like those that followed, proved unimplementable and caused lasting social, political, and economic harm. Its flaws are now widely acknowledged, yet the approach endures. Planners still prepare plans by projecting population growth, estimating future infrastructure needs, drawing rigid land-use maps, reserving private plots for public uses, imposing restrictive building byelaws, and relying on land acquisition. Though some regulations have been eased, the underlying philosophy and method of making plans remains firmly in place. Master planning ideas continue to dominate the Indian planning imagination and make planning ineffective, irrelevant or a source of dysfunction.

At the heart of the Indian planning imagination lies the belief that dense agglomeration is a problem. Planning remains driven by the goal of dispersing populations - limiting large city growth, discouraging dense urban cores, and promoting an even spread across space.

This bias shaped Delhi’s 1962 plan, which attempted to cap Delhi’s growth by developing surrounding towns and establishing a green belt around the city to restrict expansion. Internally, it tried to control population density by mandating low floor space indices and adopting a suburban morphology - buildings had to stand free on individual plots, surrounded by open land.

Plans across India replicated these measures, but failed. Cities grew regardless, densities rose, and plans were widely ignored. Today, few planners explicitly call for limiting urban growth, and FSI norms have been relaxed under pressure. Yet the urge to direct and contain city growth persists. Plans still speak of ‘shaping cities’ and enforcing ‘visions’. Building codes continue to mandate low-density layouts. Programmes like ‘rurban’ and ‘peri-urban’ development continue efforts to divert migration.

Urban planning in India has yet to fully embrace urbanisation, agglomeration, and densification. The anti-agglomeration mindset persists - in the language of plans, the design of regulations, and the thinking of planners. Until that changes, master planning will remain a barrier to India’s urban transformation.

Agglomeration economies

In the 1950s, Indian master planners misunderstood the dynamics of agglomeration. Observing the overcrowded and poorly serviced cities of the time, they concluded that dense concentrations of people and activities should be avoided. They failed to see how such concentrations generate powerful benefits that boost productivity and fuel growth.

Proximity matters. When people and firms are located close to one another, they can interact more frequently, share resources more efficiently, and exchange information more easily. Nor did the master planners grasp how strong the forces of agglomeration are – how hard it is to prevent people from moving to places where density and opportunity already exist.

This was not unique to India. Planners globally were lured by the ‘garden city’ concept which had emerged in England and quickly spread across Europe and North America. They underestimated agglomeration’s benefits and the costs of resisting it, perhaps because many were trained as architects or engineers, with limited understanding of how economies function. In hindsight, a key reason for the failure of master planning was its lack of appreciation for the power – and inevitability - of agglomeration. Attempts to block it caused immense harm not just to India’s cities, but also to the country’s broader economic development.

If Indian cities are to become engines of growth, planners must recognise that cities are, above all, landscapes of production - they are concentrations of people producing goods and services. They also support consumption, reproduction, cultural development and human flourishing, but these functions depend considerably on cities first being productive.

Urban productivity depends on whether cities can harness the many benefits that arise when large numbers of people and a large amount of capital, engaged in the production of goods and services, are closely packed and able to operate efficiently despite the close-packing. These benefits are what draw people to agglomerate. As city size increases, so can these advantages – but only if the city allows efficient interaction and exchange across the growing agglomeration.

Agglomerations also generates problems – congestion, pollution, and disease. The role of planning, then, is to help cities reap the benefits of agglomeration while continually mitigating its costs. Planning must support the urban concentration that powers economic development.

The many benefits of agglomeration

A key benefit of agglomeration is reduced transportation costs. When firms and suppliers are located close to each other, goods move more easily, making entire supply chains more efficient. This boosts productivity and often shapes the identity of the cities - Tirupur for garments, Silicon Valley for tech.

Agglomeration also expands access to labour. A firm in a large city can tap into a deeper labour market, increasing the chances of matching the right worker to the right job. But this benefit depends on efficient transport. Without it, the labour market becomes fragmented, weakening the gains of agglomeration.

Firms, especially those selling consumer goods, benefit from access to larger markets in big cities. They can grow faster while keeping the distribution costs low. Consumers, in turn, enjoy lower prices and greater choice. These mutual benefits of agglomeration explain the rise of specialised markets, where sellers of similar goods cluster together or agglomerate – offering variety to consumers and drawing in more buyers.

Underlying these benefits is the reduction in transactions costs: the extra costs involved in making economic exchanges, over and above the price of the goods or services that are being exchanged. These includes the costs of searching for information, negotiating, verifying quality, and reaching buyers and sellers. Transaction costs can add up. The prospect of reducing them by agglomerating can be a powerful factor in deciding where to locate. Shopkeepers cluster despite increased competition; people move to large cities despite their challenges – because agglomeration lowers transaction costs and improves access to jobs, customers, and services.

Co-location also intensifies competition, which in turn drives innovation – either reducing costs or the developing novel products. History offers many examples of highly innovative clusters of industries, across the world and through history. Shenzhen in China, for instance, has thousands of factories and once employed more than 2.5 million people just in the manufacturing sector.

Large agglomerations also promote a finer division of labour and specialisation. With a wider customer base, firms and individuals offering niche services can find enough demand to thrive, deepening specialisation and driving up productivity.

Another draw of large cities is the wide range of goods and services available. Early industrialisation often began in towns because they already had capital, skilled workers, banking, transport and a host of other goods and service essential for making the enterprises viable. These early advantages triggered self-reinforcing agglomeration that spurred exponential urban growth. Today, proximity to suppliers, clients, and skilled labour enables practices like just-in-time production, rapid scaling, and adaptive business models.

Agglomeration also accelerates learning and innovation through knowledge spillovers, which occur, for example, when workers carry the know-how from one job to the next. Large cities enable more job mobility and more social interaction, both of which help spread ideas – fuelling innovation in economic and cultural spheres. Today, Seoul’s advanced manufacturing ecosystem and Bangalore’s digital services cluster exemplify how the co-location of firms, workers, and ideas fosters firm-level efficiencies and ecosystem-level synergies. Innovation districts such as 22@Barcelona thrive on the proximity of universities, design schools, and industries.

In cities, many special districts and neighbourhoods - theatre districts, financial areas, cultural districts - are formed to reap the advantages of agglomeration. Concentration of people and activities also allows them to share common infrastructure - electricity, communications, transport, water supply, sewerage, storm water drainage - dramatically reducing costs and boosting economic productivity.

Economists distinguish between static and dynamic agglomeration effects. Static effects are immediate productivity gains from spatial concentration - lower transport costs, shared infrastructure, thicker markets, and easier job-switching. A garment exporter in Tirupur, for instance, can source zippers, buttons, labour, and shipping within a short radius, cutting costs and lead times.

Dynamic effects unfold over time: learning-by-doing, knowledge spillovers, reputation-building, and cumulative innovation. A health-tech firm in Mumbai, for example, may benefit not just from proximity to hospitals and engineers, but also to financiers and lawyers. While static effects are more visible, dynamic effects are more important for long-term growth. They explain why some cities keep reinventing themselves while others stagnate.

Ultimately, agglomeration is both spatial and temporal - it compounds over time. But it’s not agglomeration alone that matters, but its quality. For instance, homogeneous cities may thrive briefly but are vulnerable to shocks. Diverse cities are more resilient. Detroit’s decline illustrates this: it concentrated productivity in a single sector – automobiles - and collapsed when that sector faltered.

Problems caused by agglomeration

The close packing of people and activities driven by the benefits of agglomeration – can often lead to congestion. Streets and public transport systems become clogged, increasing travel time, while buildings can become overcrowded. Globally, as industrialisation and urbanisation began, growing city populations overwhelmed street networks and built space. Cities that expanded street networks and added floor space were able to sustain growth and continue reaping the benefits of agglomeration.

Population growth also puts a strain on urban infrastructure and amenities. Water and power supplies become overloaded, and sewers choked – creating unsanitary living and working conditions. This pattern was common in the early stages of urbanisation. Cities that invested in additional infrastructure were able to continue growing and reaping the benefits of agglomeration.

Dense settlement also increases spillover of nuisances - noise, pollution, traffic, and waste – from one person or firm to another. While some inconvenience is tolerated as the price of agglomeration, unchecked nuisances can hamper productivity. Cities must manage these negative externalities to sustain the benefits of agglomeration.

Historically, many fast-growing cities became filthy and dysfunctional before developing the institutions needed to manage these spillovers. Those that did succeeded in improving the quality of life and supporting continued economic growth.

Planning for productive cities

Agglomeration economies are not guaranteed - they must be enabled, nurtured, and regulated. Planners often see their role as designing cities from scratch, but their main task is to create enabling conditions for existing productive agglomerations.

Planning must facilitate the evolution of the built environment in existing urban agglomerations, especially when they are productive. The benefits of agglomeration depend crucially on planning interventions – appropriation of adequate land for public purposes, development of an efficient street network, regulation of negative externalities, development and provision of infrastructure and amenities, and so on.

India’s economic growth depends on the productivity of its towns and cities. To facilitate this, urban planners must first recognise the economic power of agglomeration. They must stop impeding urban growth and densification, allow cities to take their own course, and focus instead on managing the challenges that agglomeration inevitably brings.

Plans must become bare and neutral frameworks that enable cities to expand out into their peripheries and densify through the redevelopment of their already built-up areas.

Bimal Patel is Chairperson of the Board at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University. He would like to thank Suyash Rai for useful inputs.

Insight

Gated Streets, Fragmented Cities

Author: Mitali Vadher and Bimal Patel

Public streets are public goods. They are created using public resources and are supposed to be freely accessible to all – pedestrians, cyclists, vehicles and vendors alike. Their use may be regulated by public authorities but such regulations must apply equally to everyone. In contrast, on private streets, access and use can be controlled by the owners. They can gate and restrict entry. This is how it works in most cities, but not in Delhi.

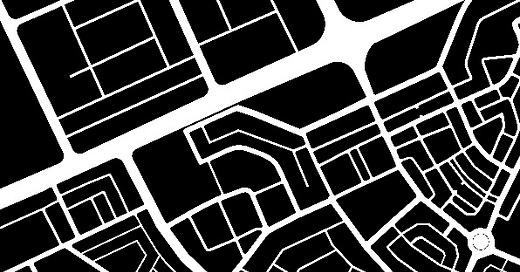

Delhi was planned bottom up. At the lowest level were clusters of houses around common amenities. A set of these clusters formed larger residential neighbourhoods and a set of these neighbourhoods, in turn, formed residential districts. Its layout, as the map below shows, comprised superblocks bounded by wide streets and divided into smaller blocks by an internal grid of narrower streets. The 100 ha area shown in the following map covers parts of C R Park, Nehru Place and Kalkaji.

Figure: (Above) The street network in a 100 hectare area spanning parts of C R Park, Nehru Place and Kalkaji. (Below) The street network in the same area, if the gated streets are omitted.

Over time however, the layout of Delhi has been transformed. Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), which manage the maintenance and upkeep of residential neighbourhoods (or colonies), have increasingly assumed de facto control over the streets within the superblocks by gating them. As one walks through such neighbourhoods it is common to come across gates with signs stating when they will be kept open and when not. Many gates are open during the day, albeit with controlled access. At night, many gates are closed. On some streets, gates are closed irrespective of the time. Though these roads remain legally public, their everyday character has become quasi-private.

The consequence of such gating is evident in the second map shown above. Of the 29.5 km of public streets in the 100 ha area shown in the above map, 11.2 kms are gated. Only about two-thirds, 18.3 km, are freely accessible. Removal of these streets from the public street network changes the character of layout. From a layout made up of relatively small blocks, formed by a dense network of wide and narrow streets, it becomes a layout of superblocks. This has two major impacts.

First, the impact on mobility and traffic. With fewer open streets, the overall capacity of the street network diminishes. Vehicles and pedestrians alike must take longer, less direct routes. Ride-hailing services often cancel trips when streets are gated and hard to access, especially at night. Congestion on the remaining accessible roads increases, and the entire system becomes less efficient. Some citizens and officials have called for these streets to be reopened, recognising that the city’s mobility suffers when public streets are treated like private driveways.

Second, the impact on civic life. Streets are not just for moving from point A to B - they are public spaces where neighbours meet, children play, and commerce thrives. They are crucial for the emergence of a shared civic life and culture. When streets are gated, they cease to function as shared public spaces and become exclusionary. The total land available for the public realm shrinks. When RWAs control access to their blocks, they also control access to public parks in these blocks which are supposed to be public spaces. All this undermines the very idea of an open, transparent city – one where public life is visible, spontaneous, and inclusive.

The motivation behind gating is understandable: residents are concerned about safety. Gating gives them a sense of control and protection. But this response creates a dangerous spiral. As more streets are gated, public visibility declines, spontaneous foot traffic reduces, and the very isolation that fuels insecurity increases. The result is a city where residents retreat behind walls into gated communities – and in doing so, weaken the shared spaces that make urban life vibrant and secure in the first place. The residents are divided on the perception of safety because of gates. Some would rather live in more open and permeable places with no gates over quiet ones with gates. Some others feel safer in gated colonies.

While Delhi’s neighbourhoods were originally designed to be walkable and connected, everyday fears and ad hoc decisions have reshaped them into something more fragmented and insular. Without a conscious effort to restore public access and reassert the civic function of streets, the city risks becoming a mosaic of gated enclaves – less accessible, less inclusive, and less functional for all.

Mitali Vadher is a Research Associate and Bimal Patel is Chairperson of the Board at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University. They would like to thank Prithika Kalaiselvan, a Research Intern at CUPDF, for research assistance.

Explained

Transaction Costs and Urban Planning

Author: Suyash Rai

Buying a home in a city is hardly ever straightforward. The process involves several steps. First, the buyers spend time and effort browsing listings, visiting properties, and comparing prices, amenities and neighbourhoods – these are known as search and information costs. Next, they negotiate with sellers – often through agents, lawyers or even informal intermediaries. These are bargaining and decision costs. Finally, even after payment, the buyer must ensure that the seller delivers as promised – on time and with the agreed features – incurring enforcement costs, such as legal paperwork and follow-up.

These efforts – searching, bargaining and enforcing – are known collectively as transaction costs, a concept introduced by Ronald Coase in his 1937 essay The Nature of the Firm, arguing that firms exist partly to reduce such costs of market exchange. For the consumer, these costs are over and above the sale price, though even that price may reflect transaction costs borne by the seller in the market exchanges involved in producing the goods and services.

Market transactions typically involve three types of transaction costs:

· Search and information costs – gathering details about goods, services or partners

· Bargaining and decision costs – negotiating terms, drawing contracts, seeking advice

· Enforcement and monitoring costs – ensuring compliance with agreed terms

In essence, transaction costs are the costs of using the market – not of the goods or services themselves, but of arranging, negotiating, and enforcing the exchange. Transaction costs can snowball – the transaction costs incurred at each stage of production are built into the price of the product, which is then used to cover the costs of the next stage of production. Ultimately, the consumers pay for all such costs.

Why transaction costs matter for cities

Transaction costs offer a powerful lens for understanding why cities exist and how well they function. A dense, well-organised city reduces search costs (by offering many options within a compact area), bargaining costs (through better coordination), and enforcement costs (via shared rules and institutions). The productivity of a city – how easily people can live, work, trade, and innovate – depends on how low these transaction costs are. They are embedded in everyday activities: buying a house, hailing a cab, building a factory, or applying for permits.

Why should urban planners and designers learn about transaction costs? For one, urban planning itself derives much of its justification from its role in reducing them. Cities are arenas of complex economic and social exchange, where transaction costs can hinder efficient interactions. Planning can help mitigate some of these costs.

When use of land for noxious purposes creates externalities for others, in theory the problem could be resolved through private negotiation (and compensation), but in practice, high transaction costs for such negotiations often prevent this. Planning intervention can help regulate such effects.

Individual actors may wish to coordinate for shared goals - such as establishing an industrial park where firms cluster together - but this requires negotiation, mutual trust, and aligned expectations, all of which involve transaction costs. Planning can reduce these costs by pre-designating such spaces and providing common facilities, thereby making it easier for firms to locate and invest.

Similarly, high transaction costs often prevent beneficiaries of infrastructure from coordinating to get it built. These costs include identifying other beneficiaries, negotiating terms, and enforcing agreements. Planning can overcome these barriers by enabling the provision of infrastructure without requiring each beneficiary to bear the burden of coordination.

Landowners and investors often incur high costs in obtaining and verifying information about current and future land use. Planning can lower these costs by offering legal certainty and transparent, reliable information about land use regulations and future development plans. This can enable more productive and confident investment in land.

However, planning can also impose transaction costs on urban markets. To remain mindful of this, urban planners can use the transaction cost lens in two ways: first, by evaluating how planning decisions directly create or reduce transaction costs in urban markets; and second, by reflecting on how planning might indirectly shape transaction costs across broader urban life.

Direct consequences of urban planning

Planning directly shapes the transaction costs in markets that produce the built environment. Consider a builder developing and selling apartments. From their perspective, many regulatory compliance steps function as transaction costs, as they enable or complete market exchanges. Obtaining permits and clearances involves search and information costs. Structuring agreements with buyers in line with regulations entails bargaining and decision costs. Registration, stamp duties, and formal handovers constitute enforcement and monitoring costs.

When procedures for obtaining building permissions are complicated or unclear, developers face high bargaining and decision costs, often needing intermediaries to navigate the approvals process. Complex and inconsistent regulations increase search and information costs, requiring significant legal and technical expertise just to interpret what is allowed. Moreover, the requirement to secure numerous permissions and NOCs – from aviation, environmental, coastal zone, and other authorities – adds layers of search, decision, and enforcement costs. These cumulative burdens extend timelines, increase risk premiums, and discourage investment, particularly from smaller or less connected actors.

These are not part of the cost of creating floor space itself, but they raise the total cost of producing and transacting in the real estate market. Other planning domains also impose similar costs. For example, in transport planning, the absence of real-time parking information creates search costs for drivers. These burdens often stem from design and implementation choices made during the planning process.

Some of these costs are unavoidable, but planners should pay close attention to the direct costs they impose on the building process.

Indirect consequences of urban planning and design

Urban planning also indirectly shapes transaction costs across all urban markets by influencing the built environment. Poor planning – such as fragmented urban form, inadequate transport systems or poor land-use integration – raises the cost of everyday transactions across sectors. Retailers may face logistics delays due to congestion, while jobseekers may miss opportunities because they cannot reach certain areas of the city within a reasonable commute time. These transaction costs do not arise within individual markets, but from the wider urban context in which all markets operate. In a poorly planned city, information is harder to obtain, negotiation is more difficult, and enforcement is weaker. This friction undermines activity in finance, labour, services, and more.

Urban design also matters. When pavements are well-maintained and continuous, the time and effort required to make short trips – such as walking to the market – are significantly reduced. This lowers the search and mobility costs for individuals, especially in dense urban areas where economic exchanges are frequent. Similarly, when cities provide well-organised, accessible spaces for neighbourhood vegetable markets, they reduce the search and bargaining costs for both buyers and sellers. Vendors can rely on a steady flow of customers, and consumers benefit from predictable locations and prices, minimising the time and uncertainty involved in daily shopping.

Conversely, transaction costs rise when streets are poorly designed, leading to traffic congestion, long commutes, and unpredictable travel times. These inefficiencies limit the potential for spontaneous interactions, deter investment, and reduce the overall efficiency of urban markets. Thoughtful urban planning and design can reduce such frictions and enable more seamless economic and social exchanges.

Some of these might seem like small costs, but when we view the city as an interconnected economic system, these can add up to significant transaction costs. For instance, a city that fails to enable mobility allowing all workers to reach any part of the city within an hour effectively fragments the labour market – or worsens the quality of life for workers who end up spending too much time commuting. A fragmented labour market is inevitably less efficient than an integrated one.

Towards a transaction cost–sensitive urban planning

As Edward Glaeser argues in Triumph of the City, cities are productive because they bring people together, enabling the exchange of ideas, learning, and collaboration – especially in industries where human capital and knowledge spillovers drive innovation and economic growth. Transaction costs are the friction within these interactions. Cities that minimise such frictions become vibrant and inclusive; those that don’t risk becoming exclusionary and sluggish.

From this perspective, urban planning is fundamentally about reducing friction in economic and social exchanges. It should be viewed through the lens of transaction costs. Planning that succeeds in lowering these costs can, by improving affordability and mobility, enhance efficiency across all urban markets.

Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Reading

Governing the 21st Century City-Region: Lessons from the BRICS

Author: Suyash Rai

Urban regions are not only engines of economic growth but also arenas of political contestation, social change and institutional experimentation. In the Global South – especially in Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (the BRICS) – urbanisation has outpaced governance capacity. These vast city-regions, now encompassing tens of millions of people, integrate rural hinterlands, suburban sprawl and commercial cores into dynamic, often chaotic systems.

How do such mega city-regions govern themselves? What institutional arrangements manage transport, land use, housing, water and economic development across fragmented jurisdictions and conflicting agendas? Philip Harrison’s Governing Complex City-Regions in the Twenty-First Century offers grounded answers to these questions. Rather than prescribing neat solutions, Harrison examines the messy, layered realities of governance in five sprawling BRICS city-regions.

Harrison writes that he initially approached the research deductively but soon found that universal concepts such as ‘city-region’ proved inadequate due to the different linguistic, scholarly, political and institutional traditions across the countries. This prompted a shift to a more inductive approach, starting with the distinctiveness of each context and how language and meaning are constructed locally. Even the term ‘city-region’ varies in meaning – from Malmö in Sweden to China’s Yangtze River Delta.

The city-region as a unit of governance

One of Harrison’s core arguments is that the traditional boundaries of cities and municipalities don’t reflect how urban systems actually function. The city-region – an urban formation that includes the city and its surrounding towns, suburbs and peripheries – is increasingly the scale at which economic life unfolds. People live in one jurisdiction, work in another, and commute through a third. Infrastructure, environmental risks and labour markets rarely respect administrative lines.

The hyper-complexity of these city-regions creates uniquely challenging collective action dilemmas. Harrison describes large city-regions as ‘talking pigs’ – extreme cases of hyper-complexity due to their size, dynamism and indefinite boundaries. Modern governance, constructed within demarcated territories, is constantly tested by urban expansion across jurisdictions. This expansion demands either the continual redrawing of boundaries or the creation of other mechanisms for joint action.

Harrison notes that institutional fragmentation makes it difficult to manage externalities, spillovers, and common property resources. Effective solutions require cooperation – and cooperation depends on trust. Trust required for cooperation can be gradually improved through repeated interactions, where every participant gains.

In China, the state possesses both the authority and capacity to plan at the city-regional scale. In India, by contrast, the fragmentation is profound. Mumbai’s metropolitan region is governed by dozens of agencies and local bodies, with overlapping jurisdictions and little coordination. Harrison doesn’t claim that one model is better than the other, but he calls for taking governance at the city-region level seriously - certain problems need to be addressed at that scale.

Institutions matter, but they emerge

Harrison argues that institutional processes are not consciously designed but arise through gradual, interactive and adaptive problem-solving. He contrasts this with ‘deliberate practices’ and acknowledges that urban governance is replete with ‘institutional blueprints that have gone awry’. Emergence can lead to routines that evolve into enduring, seemingly designed formations.

Across the BRICS cases, a recurring theme is institutional layering. New governing bodies are created without dismantling the old ones. Agencies multiply. Policies contradict each other. And often, institutions are captured by entrenched interests.

Consider São Paulo: despite formal planning frameworks and participatory processes, land use is still driven by political deals. In Johannesburg, post-apartheid integration efforts coexist with elite-led development and informal governance. Existing institutions are products of historical compromises and political bargaining, not rational design.

Informality is not the exception

One of the central insights that emerges from Harrison’s efforts to study the contextual embeddedness of governance arrangements is that informality is about governance itself, and not just something that exists on the margins. In many of the city-regions Harrison examines, informal institutions play a central role in decision-making. Local leaders, political brokers, resident associations, NGOs – and even criminal networks – often play critical roles in shaping land use, service delivery and infrastructure access.

This is not a call to romanticise informality. Any serious urban strategy must engage with these actors and understand how informal governance actually works on the ground. Formal planning frameworks often assume a level of state capacity and authority that simply doesn’t exist. Ignoring informality doesn’t make it go away – it just pushes it further underground.

In contexts driven by informality, institutional reform cannot rely on changing rules that have little real impact. Effective reform requires understanding the ecosystem of power, incentives and informal practices. Those looking to restore the relevance of formal institutions must address the underlying issues of legitimacy and capacity, and then solve the problems that informality creates.

For instance, in systems shaped by informal deals, public interest is often neglected. If building permissions are granted without due regard to protecting the public realm, the city will have a shortage of roads, parks and amenities. But these shortcomings offer planners an opportunity to demonstrate their problem-solving capabilities. Planners must also be strategic. Building coalitions, navigating politics, and managing trade-offs are just as much a part of planning as making maps or writing regulations.

Lessons for Indian cities

For Indian city planners and leaders, Harrison’s book is both familiar and instructive. Many of the problems it highlights – fragmented governance, informal settlements, multiple agencies, weak coordination – are features of everyday life in cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore. But the book also offers ideas that planners and leaders would do well to take seriously:

First, there is a need to identify and address governance and planning problems at the level of city-regions. This means developing mechanisms that either achieve cooperation across the governance institutions in these city-regions or serve as overarching institutions empowered to solve problems that can only be solved at that scale. The suitable approach may vary based on context.

Second, it is important to understand and engage with informal governance. Planning and governance will continue to falter unless they understand and work with the actors who actually mediate urban life, partly because of failures and limitations of formal institutions. Restoring the salience of formal institutions will require understanding why informality emerges and addressing the gaps that informal processes leave behind. It may also require working with informal institutions for some purposes.

Third, in city-regions governed by a multiplicity of independent institutions with overlapping jurisdictions, it is necessary to consider the incentives for cooperation. As experience has shown, such polycentricity in governance is not a problem by itself, but it can become dysfunctional when the costs of cooperation and collaboration exceed its benefits.

Judgement over templates

Governing Complex City-Regions doesn’t offer a grand theory or a universal model. It proposes a way of thinking about city-regions that foregrounds history, politics and institutional complexity. It reminds us that governing large urban regions is not about finding the right toolkit or importing the best practice from elsewhere. It is about exercising judgement –understanding what is possible, knowing who to work with, and finding ways to move forward, even under imperfect conditions.

Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University