#2: Urban Planning Knowledge | Urban Morphologies | Order Without Design

An essay on the knowledge needed for urban planning, an insight on urban morphologies, and a recommendation to read a book on how urban planning can benefit from urban economics.

Essay

The Knowledge that Urban Planners Need

Authors: Bimal Patel and Suyash Rai

As discussed in the previous issue of this newsletter, urban planning is a complex public policy challenge. It involves state interventions that improve the functioning of market processes to ensure the emergence of good urban built environments. Improving the practice of urban planning in India will require achieving the right balance between what markets can do and what planning should do. This balance needs to be reflected in all the instruments of state intervention – from the primary planning laws, which define the scope and powers of planning, to urban plans, zoning regulations, development control regulations, and so on.

In some domains, the government in India has redefined its role to move away from state control to focus on certain development and regulatory functions that the markets themselves do not perform well. Mere removal of state intervention is not enough – a system needs to be developed with sophisticated capabilities to choose the right kind of state interventions and to implement them well. Without such a system, one step towards deregulation may be followed by imposition of other unnecessary restrictions. More importantly, markets typically cannot function well without the state playing certain development and regulatory functions.

Consider the equity market reforms in India, which are widely seen as successful. Merely dismantling the older framework, which worked with a very different set of beliefs about the state’s role, was not enough. A new institutional framework for development and regulation was required for the markets to thrive. The replacement of the Controller of Capital Issues (CCI) by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) marked a transition from a state-controlled regime to a market-driven regulatory framework. This was done through the repeal of an old law and the enactment of a modern law. Suitable infrastructure for security markets – modern exchanges, depositories, and clearing corporations, among others – and a judicial tribunal to serve as a check on the regulatory agency were also built. In addition, the regulatory process also became more participatory.

This meant that even as the state defined a more limited role for itself – that is, limited to facilitating the development of infrastructure and regulating the markets – the number of development and regulatory activities proliferated, and so did the number of professionals working in those state or quasi-state agencies that were involved in them. When the state sought to command and control, the number of persons and agencies required was much smaller because the capabilities required were quite limited. CCI was a small, bureaucratic setup under the Ministry of Finance, Government of India. SEBI is a much larger agency, employing more than 1,000 officers as of March 2024, even though many regulatory functions in securities markets are performed by market infrastructure.

In essence, a system of state control was replaced by a system of development and regulation aimed at helping markets work better. The regulatory agency became an essential and empowered participant in a complex system where different constituents – government, businesses, consumers, civil society and academic institutions – play interlocking roles. A key insight is that the development and regulation of markets requires knowledge that cannot be produced by the regulatory agency working in isolation. A broader regulatory system is required to create and refine this knowledge.

In a similar vein, reforming urban planning is also as much about reimagining the ideas that underpin its practice as it is about rebuilding the urban planning system in which planners work. We need to consider the capabilities, procedural integrity and accountability of planning in this broader system. Urban planners should be seen as coordinators and decision-makers in this system, which creates the knowledge needed for identifying and solving problems related to the built environment of cities. What kind of knowledge do the planners need to be able to take the right decisions?

What urban planners need to know

Since urban planning is meant to regulate the markets and activities that create urban built environments, first and foremost, planners need an understanding of how such markets work. In addition, they require an appreciation of what markets do well, how easy it is to distort their functioning and the harm caused by doing so. Next, since urban planning is essentially a public policy challenge, planners require a deep understanding of what makes for good public policy. They need an intuitive understanding of public economics, the subject that deals with the impact of government policies on economic efficiency and equity. Planners also need an intuitive understanding of political economy – the intersection between politics and the economy – to realistically understand the ideas, incentives, and behaviours of politicians, public officials, and citizens, which both enable and limit government action.

Planners also need a practical understanding of the institutional context in which they operate. They must know the extent of their statutory mandate, as well as the government’s actual capacity to enforce and implement plans and regulations. Keeping these in mind, planners must be able to decide what aspects of people’s building decisions it makes sense to regulate and what aspects are better left for them to decide. Planners must be able to craft plans and regulations that do not compromise efficiency, trample on property rights, distribute costs and benefits unfairly, thwart economic growth, overburden people’s capacity to pay or lead to unintended perverse outcomes.

Since the objective of urban planning is to ensure the emergence of good urban built environments, planners need architecture, landscape design, urban design, civil engineering, municipal engineering or transport engineering abilities. Those with architecture, landscape design or urban design backgrounds must be able to draw up city layouts with efficient street networks, a meaningful arrangement of buildings, and networks of gardens, parks, plazas, promenades, playgrounds, and other common amenities. They must also be able to formulate regulations to structure meaningful and efficient urban morphologies. Those with civil, municipal or transport engineering backgrounds should be able to design efficient and resilient water supply, sewerage, storm water or transportation systems. The vast array of technical skills that urban planning requires means that, by necessity, it is a variegated profession. Planners, like doctors, are hyphenated professionals – there are architect-planners, infrastructure-planners, transport-planners and so on. Here too, although urban planning requires architecture, urban design, civil engineering, municipal engineering or transport engineering skills, it should not be assumed that planning can be reduced to those disciplines.

Competence in urban planning requires specific professional training as well as apprenticeship with experienced professionals. No amount of experience in allied professions such as public administration, urban management, urban design, municipal engineering, transport engineering, economics or public finance can substitute for a deep familiarity with the nitty-gritty of the statutory mechanisms that urban planning uses. These include development plans, zonal plans, town planning schemes, local area plans, land use zoning, development control regulations, volumetric building controls, transferable development rights, heritage and environmental listings, land acquisition, impact fees, betterment levies and development charges. It is only by deftly using these mechanisms that planners can do all the things that are necessary for securing planned development: appropriate land, control location of activities, regulate building construction, protect vulnerable neighbourhoods and environments, provide public infrastructure, and raise resources to help build cities that allow good and flourishing lives.

Urban planners as policy makers

In India, urban planning is often seen as a design discipline. However, to serve its purpose well, it should be seen as a public policy discipline. Urban planning is neither a technocratic pursuit in the manner that engineering is nor an academic discipline in the manner that economics is. Planners must make decisions that have an immediate impact on the built environment, for example, the alignment and width of a street, the height of buildings, the alignment of a water supply line and the route of a metro line. Urban planning is a technically rooted, locally grounded, public policy pursuit that requires the use of practical skills and professional judgement learnt through practice. In dealing with urban planning problems, planners must deal with tricky public policy matters, complex design issues and local realities from within imperfect institutional settings. They must make difficult trade-offs that affect multiple stakeholders while upholding the public interest.

To be effective in serving the public interest, urban planners also need a variety of soft skills and ethical commitments that help them navigate the complex political economy and institutional landscape in which they operate while upholding the values that should guide their work as professionals. Among the most important skills required are the collaborative skills of being able to work with and learn from other people. No plan made by a planner operating in isolation can work. This ability to work collaboratively and to learn continuously relates to the types of knowledge that urban planners need.

Some problems are commonly encountered and not particularly context-specific. The knowledge required to solve them is readily available or can be easily acquired. Other problems are unique to contexts on account of their geography or social conditions. Yet others are newly emergent problems that no one has encountered earlier. In both these cases, new knowledge must be generated. To be able to do this, urban planning has to be a reflective practice that is able to adopt innovations, examine their efficacy, discard them if necessary and adopt alternative innovations. Its underpinning philosophy must be fallibilistic, and planners have to steer away from a search for utopian solutions.

An advantage of later urbanisation is that one can learn and adopt lessons from other places. Many countries are now almost fully urbanised. A very tiny proportion of their population lives in rural areas. In the process, they have countered many problems and solved them, often by trial and error. Countries that are urbanising now have the advantage of learning from their experience. Planners can benefit from having a good understanding of the history of planning in India and in other countries. However, at the same time, it should be kept in mind that this knowledge cannot be directly employed in any context as ‘best practices’. The task of exercising one’s judgement regarding which solutions work in a given context remains with the planners and their collaborators.

To be able to develop and deploy the planning techniques, planners need a broad worldview about how the world works and their role in it. Some aspects of this worldview have been discussed earlier in this essay: a sound understanding of the respective roles of planning and markets, a knowledge of applied public economics, an understanding of relevant political institutions, and so on. In addition, the worldview of a planner should also guide the approach they bring to the tasks of urban planning. They should start by making modest assumptions about how well they can predict the future, how much they can understand preferences, how accurately they can foresee people’s adaptive responses to their plans and regulations, and so on.

To take the right decisions, planners also need knowledge of the context in which they are operating. The built environment of cities co-evolves with markets, society and political institutions. No two cities can work with the same plan, as their contexts differ in important ways. Therefore, a good planner needs to be deeply knowledgeable of the city in which they are working. Urban planning requires locally grounded planners who have an intimate understanding of ground realities. This is why it is impossible to develop plans from a remote location. Planning should mostly be done locally in a city, with some constraints imposed from higher levels of administration for specific purposes, such as addressing the problems of externalities that a city may impose on other areas. This means that cities should have the power and the capability for urban planning, with opportunities to learn from other cities.

Conclusion

The urban planning system should support planners by creating and refining the knowledge they need. The system comprises various stakeholders who complement each other and act as checks against each other’s excesses. The most important of these are government departments and authorities, private sector firms, academic institutions, professional organisations and civic associations. Tackling the challenges of urban planning requires well-trained and competent planners, applying context-specific knowledge to solve planning problems, and working with an array of stakeholders that complement and reinforce one another. In the next issue of this newsletter we will present some ideas on how the urban planning system could be reimagined to help improve the practice of urban planning in India.

Insight

The Significance of Urban Morphologies

Authors: Bimal Patel, Niki Shah, Shweta Modi

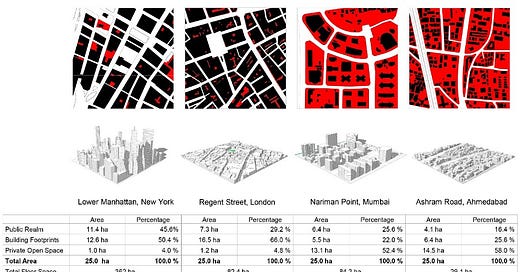

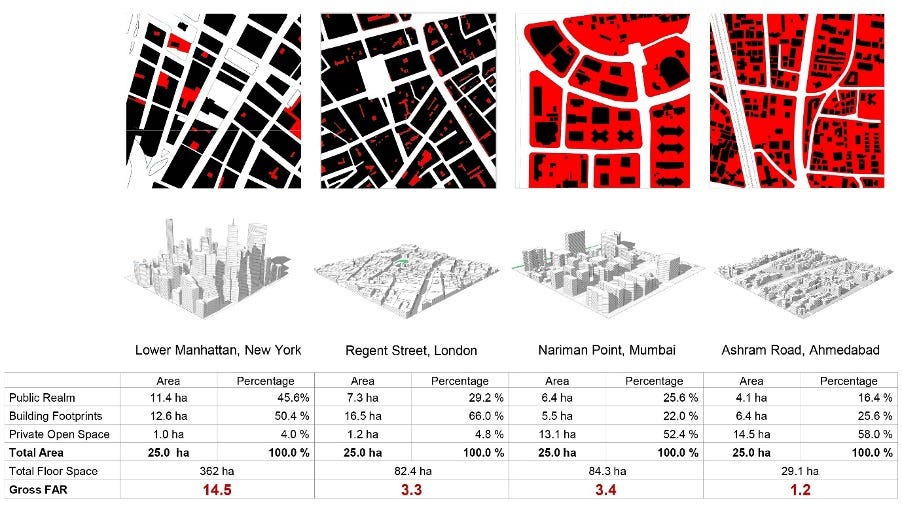

The figures above show 25 hectares in the center of New York, London, Mumbai and Ahmedabad. The maps show land devoted to public streets and parks in white, land covered by buildings in black, and private open land in red. The axonometric diagrams show buildings in the area and give a sense of the morphology. The morphology of New York and London is made up of buildings covering entire blocks and fronting directly onto the street. New York has a high-rise urban morphology while London has more of a low-rise urban morphology. Mumbai and Ahmedabad’s morphology is made up of buildings standing free within plots. Both have a suburban morphology. In comparison to Ahmedabad, Mumbai has more high-rise buildings. Therefore, Mumbai has a high-rise suburban morphology, and Ahmedabad has a low-rise suburban morphology.

The tables below each example show the distribution of land use in each of the four examples and the amount of floor space there. The floor area ratio for each of the examples is shown last, which is the total amount of floor space divided by the land area, which in this case is 25 hectares. It lets us compare how intensely land is used in each of the cases.

New York in the area shown here uses a high-rise urban morphology. It has an FAR of 14.5. It also leaves a generous 45 percent of the land open for the public domain. London has an FAR of 3.3 even though its buildings are relatively low rise. It too leaves 30 percent of its land open for streets and parks. The morphologies of Mumbai and Ahmedabad being suburban, they are not able to pack in large amounts of floor space. Mumbai, even with its high-rise buildings, is only able to pack in as much as low-rise London. It also does not have as generous a public realm as London or New York. Because it is low rise, Ahmedabad has even less floor space and has a meaner public realm.

Such an analysis of urban built environments recognises the fact that life in cities requires floor space not just land. Open land is required for streets, parks, playgrounds and other such spaces. However, it is the amount of floorspace that is crucial because people in cities need floor space to live and work. Moreover, the density of floor space also matters. This is because productivity of people living in cities depends crucially on how easily they can interact with one another and how large the pool of people they are able to easily interact with. Urban built environments that pack vast amounts of floorspace within them can house large numbers of people in close proximity. For people to be able to easily interact with each other and also live well, built environments also have to be structured in a way that ample land is left open for streets and parks. Morphology has considerable bearing on both - the density of floor space and on the generosity of the public realm.

Urban morphologies are outcomes of planning. Regardless of whether planners are conscious of it or not, they emerge from a city’s land use plan and building regulations. They determine how land is used and limit the amount of floor space that can be built. The actual amount that is built is of course determined by market forces. If Indian planners want India’s cities to be liveable, efficient and productive, they have to pay attention to the kind of morphology they are mandating through their land use plans and building regulations.

Reading

How Urban Planning Can Learn from Urban Economics

Author: Suyash Rai

Building good built environments in cities requires a balance between planning and markets. Cities must continuously strike this balance, lest they go too far in either direction. The knowledge of urban economics can help planners achieve this balance by helping them better understand the way markets work, and how design interventions work. There is a growing body of knowledge to learn from. While much of it is from the global North, a sophisticated consideration of this knowledge can feed the intuition of those looking to shape cities in the global South. Developing countries also need to invest in creating this knowledge in their respective contexts.

Alain Bertaud’s Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities is an essential read for anyone interested in urban planning, economic development, and the intersection of markets and planning in shaping cities. Bertaud, a seasoned urban planner with decades of experience in cities across the world, argues that urban planning should be grounded in economic principles rather than rigid, norms-driven master plans. He demonstrates how cities function as labour markets, where the efficiency of land use, transportation, and housing supply directly impacts economic productivity and social mobility. By integrating urban economics into planning, he provides a compelling case for policies that allow cities to evolve dynamically rather than be constrained by overly prescriptive regulations.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is its empirical foundation. Bertaud draws on case studies from cities around the world - ranging from New York to Mumbai - to illustrate how different planning approaches lead to vastly different outcomes. He highlights the unintended consequences of restrictive zoning laws, excessive land-use regulations, and poor infrastructure planning, showing how they exacerbate problems like congestion, unaffordable housing, and inefficient land use. He makes a strong argument for leveraging market forces to improve urban liveability, emphasising the need for flexibility in planning rather than top-down control. Focusing on the objectives of mobility and affordability, Bertaud offers many ideas on how planners could make better choices.

Order without Design is particularly relevant for city leaders and urban planners. Bertaud challenges conventional planning wisdom by advocating for a market-driven, data-informed approach that prioritises adaptability and efficiency. His insights are especially valuable for rapidly urbanising countries, where poorly conceived regulations can stifle growth and deepen inequalities. Treating cities as dynamic economic entities rather than fixed blueprints, the book provides a pragmatic framework for fostering sustainable and prosperous urban environments.

I recently explored a similar concept in my latest post where I lay out why Chandigarh is a bad example for urban design.

One more thing I'd like to add here is that the higher the Floor Area Ratio, the more dense a city is and each piece of infrastructure can serve far more outdoors otherwise. In a poorer country like India, that ends up giving you more bang for the buck.

I'd also like to recommend two books:

Jane Jacobs' The Death And Life of Great American Cities and James Scott's Seeing like a State.

Both these books talk about city planning from the view of a resident that experiences the city rather than an urban planner that views it from an airplane and focuses on the aesthetic.