#8: The Parking Problem | Regulations and Common Facilities | Public Goods in Cities | Making of Hong Kong

An essay on tackling India’s parking problem, an insight on regulation of common building facilities, an explanation of urban public goods, and a book recommendation on Hong Kong’s built environment.

Essay

Tackling the Parking Problem

Authors: Bimal Patel, Rutul Joshi, Suyash Rai

The demand for parking has been steadily mounting in India’s towns and cities as more people are able to afford vehicles. With limited dedicated parking spaces, streets and open spaces are increasingly occupied by parked vehicles – choking traffic, reducing street capacity, and encroaching on plazas, playgrounds and gardens. The parking problem has become a serious urban issue that is set to worsen. Addressing it requires a rethink on parking policy that works on both demand and supply. This essay offers an approach to achieving this efficiently and sustainably.

How much does parking cost?

Parking requires space – whether on the ground or in structures. But how much space, exactly? This depends on the type of vehicle. A good starting point is to use the average passenger car as a reference, and to define the requirements of two-wheelers in terms of fractions of passenger car units (PCU). Larger vehicles such as buses and trucks can be separately considered.

Off-street parking

A standard, bare parking slot measures 2.5 x 5 metres (12.5 sq m). Parking also requires driveways for access and manoeuvring. In efficient layouts – with right-angle parking and double-loaded driveways – a 6-metre driveway adds around 7.5 sq m per car, bringing the total to roughly 20 sq m. When factoring in approach roads and entry/exit points, the space needed per car in large, efficient parking lots ranges from 22.5 to 25 sq m.

Multi-level garages require even more space per car due to the inclusion of ramps in addition to driveways. The area requirement increases further when layouts are constrained by structural columns and walls. Purpose-built, multi-level structures designed for efficiency usually need about 35 sq m per car. In basement parking beneath office buildings – where columns are spaced more widely – this rises to around 40 sq m. In residential apartment buildings, the space required can reach up to 45 sq m per car.

The cost of off-street parking includes construction and land costs. While construction costs for parking are somewhat lower than those for habitable spaces, the difference is not significant and can largely be ignored. Thus, parking in buildings costs roughly the same as the habitable real estate in that building. In dedicated parking structures or lots, the cost is equal to the real estate value of the surrounding area.

Parking a car in an apartment building typically requires around 45 sq m. This means providing parking for a 100 sq m apartment adds nearly half to its cost. In large office buildings, where the average employee occupies about 15 sq m, allocating a parking space of about 40 sq m per employee would consume over two-thirds of the building’s floor space for parking. Even with efficient surface parking that uses 30 sq m per car, the parking lot would need to be twice the building’s floor area. While this may be feasible in the suburbs, it is prohibitively expensive in city centres where land is expensive.

On-street parking

On-street parking is usually provided in slotted bays along the carriageway, with cars parked either parallel or at an angle, depending on bay width. Lanes may be widened slightly to ease manoeuvring in and out of parking slots. Because the carriageway serves both traffic and parking access, the space allocated to on-street parking is essentially just the area of the parking slot – 12.5 sq m per car.

The cost of on-street parking includes land and paving. While land cost varies by location, paving a 12.5 sq m parking slot typically costs between Rs. 25,000 and 35,000, depending on materials and durability. Where land is expensive, the cost of paving is relatively small. More importantly, street space is limited and must also accommodate footpaths, traffic carriageways, vendors, infrastructure and trees. As a result, decisions about on-street parking depend more on these trade-offs than on the real estate cost of on-street parking.

Why the current parking policy does not work

Every vehicle needs parking when idle and at its destination, meaning ownership inherently creates parking demand. From a public economics perspective, parking is a private good – excludable (access can be controlled) and rivalrous (one person’s use excludes others) – whether on- or off-street. Therefore, it is best allocated through markets, with individuals buying or renting spaces from private providers or public authorities. Proper pricing allows consumers to factor parking costs into their decisions around vehicle ownership and use.

This is not how parking is treated by authorities in India’s towns and cities. They tolerate free use of public streets and open spaces for parking and assume governments must ensure ample, often free or subsidised, parking for all. Development Control Regulations (building regulations) mandate minimum parking in buildings, and authorities invest in public parking facilities, often pricing them well below cost. These policies are problematic.

First, free public parking, minimum parking mandates, and public investment in parking infrastructure reinforce the perception that parking is an entitlement. Unpriced on-street parking encourages informal – and often illegal – appropriation of public space, undermining the rule of law. It also discourages the emergence of private providers of parking services.

Second, free or underpriced on-street parking subsidises private vehicle owners at public expense, shifts private costs onto taxpayers, and negatively affects urban mobility. It rewards early arrivals and penalises others, creating inequities in public resource allocation.

Third, free or subsidised parking promotes vehicle ownership and use, worsening congestion and pollution, and weakening the viability of public and intermediate public transport.

Fourth, minimum parking requirements encourage developers to bundle parking with habitable space, thereby distorting both real estate and transport markets, inflating property costs, and encouraging vehicle ownership even among those who might otherwise rely on public or non-motorised transport. Bundled parking introduces psychological and financial sunk costs: once a household purchases a property bundled with parking, it may feel compelled to acquire a vehicle to ‘justify’ the expense. Minimum parking requirements typically stem from concerns about spillover onto public streets. But this assumes on-street parking is free or subsidised. When properly priced, this rationale is significantly weakened.

Fifth, free on-street parking reduces the space available for traffic lanes and footpaths. Using public open spaces for parking steals land from parks and playgrounds – already scarce in Indian cities, which usually devote less than 15% of their land to streets and less than 5% to parks, about half of what comparable cities worldwide provide.

What policy reforms are needed

Public authorities must recognise that parking is not a public entitlement but a private consumption choice. Well-functioning parking markets – supported by appropriate pricing and flexible regulation – can lead to better decisions by everyone. A sound parking policy rooted in such an approach would have the following features:

Free use of public land for parking would be disallowed. Priced on-street parking would only be allowed where more important competing uses are not compromised. On busy streets with high pedestrian volumes or public transport usage, on-street parking may be prohibited altogether. On secondary streets, parking may be allowed but priced at levels that ensure reasonable turnover and accessibility. Dynamic pricing models could be used to maintain availability, for example by targeting 85–90% occupancy rates to reduce cruising and ensure that spaces remain consistently available.

Public resources would not be used for the creation of subsidised parking facilities.

Development Control Regulations would not mandate minimum parking requirements, leaving it to building owners to determine how much parking to provide.

Such a policy would serve five important public purposes:

First, ending the use of public land and public resources for building parking facilities would promote fairness. The private costs of vehicle ownership would be borne by those who choose to own vehicles, not by the public. In a city, only a small percentage of residents own cars, most of who are likely to be better off than the other residents. It is unfair for public resources to be disproportionately allocated to them.

One counter-argument is that parking charges may hurt people who earn a living using vehicles parked in public spaces. However, this concern misunderstands the effect of such policies. If uniformly enforced city-wide, parking costs would be passed on to the users of these services. Moreover, free parking shifts the cost onto everyone, including those not using such vehicles for their livelihood.

Second, providing priced parking on public land only where more important competing uses are not compromised would ensure that meagre land in the public domain in Indian cities is used in a fair and efficient manner.

Third, unbundling parking from other property would allow buyers and renters to make independent choices about vehicle ownership and parking needs. Households would have more flexibility in allocating their resources. Businesses, too, would benefit from flexibility. Some firms may find it more efficient to provide shuttle services, reimburse ride-hailing expenses, or adopt flexible work arrangements instead of investing in expensive parking infrastructure. Others may choose suburban locations where ample parking can be provided at lower costs.

Fourth, disallowing free use of public land for parking and unbundling parking from property would encourage private provision of commercial parking garages. This would allow parking to be bought or rented separately from other property, introducing flexibility into real estate and transportation decisions. Some existing private spaces might get converted into dedicated parking garages, while some others – especially in new construction projects – may choose not to provide much parking. This would also allow parking to become a specialised economic activity rather than something everyone does.

Fifth, a reoriented parking policy would integrate mobility and parking into a comprehensive framework that weighs trade-offs and guides decisions towards improving urban mobility. Since parking can also happen off-street, streets should prioritise the movement of people and goods rather than vehicle storage, and a clear consideration of trade-offs would ensure road space is not arbitrarily given for parking. This would also lead to a more efficient decision-making process about vehicle ownership and usage. People would consider the full costs while planning to purchase a vehicle, and make careful choices while deciding to take trips – preferring to combine trips or use other modes of transport. This shift in behaviour could help improve mobility.

In conclusion, the lack of parking and the consequent loss of public space to parking has become a serious urban problem. Given the way parking policy is currently structured – allowing unregulated and free parking on streets, and mandating building developers to provide specified amounts of parking – the problem is bound to worsen.

City residents’ expectations - apartments with parking, free or inexpensive roadside parking - have been shaped by the policy environment in which they have lived. These expectations are not immutable; residents in many other countries hold very different assumptions. The policy reforms discussed above can gradually reshape these expectations over time.

Cities must reorient their parking policies to create a framework that incentivises the supply of parking by commercial providers and limits demand for public parking by pricing it properly. They must stop allowing free parking on public streets and open spaces, stop sinking public resources into the creation of subsidised parking facilities, and stop mandating that building developers provide specified amounts of parking.

Rutul Joshi is Senior Associate Professor at CEPT University. Bimal Patel is Chairperson of the Board and Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Insight

Building Regulations for Common Facilities

Authors: Avanish Pendharkar, Anju Pillai, Gauri Shelar

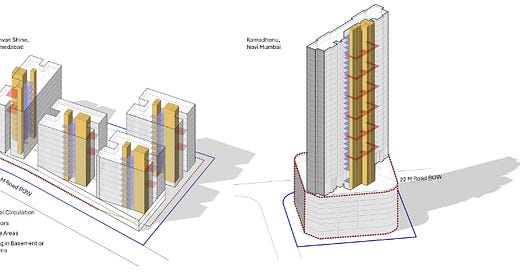

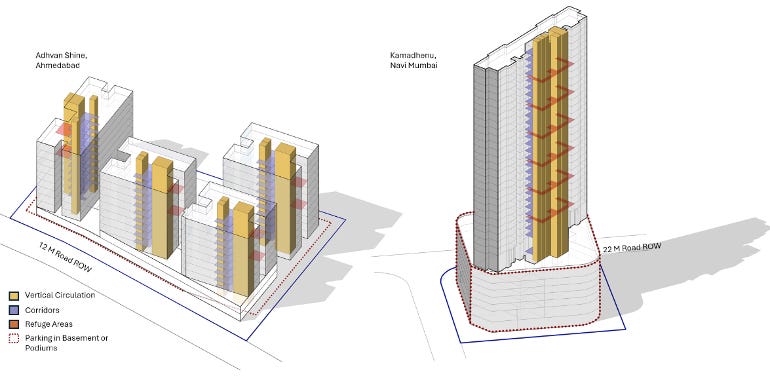

In the previous issue, Namandeep Verma explored how building bye-laws regulate how much of a plot has to be left open and how much can be built upon, thus regulating the use of land in any city. This article focuses on building bye-laws that regulate the size of common facilities in apartment buildings – vertical circulation (stairs and elevators), passages, fire refuge areas and parking. It compares the share of common facilities in the overall built-up area of two recently constructed apartment complexes, one in Ahmedabad and the other in Navi Mumbai. Buildings in both complexes comply with building regulations currently prevailing in the two cities. The comparison reveals which of the two regulatory regimes imposes higher mandatory costs and by how much.

The figure below shows the two building complexes. Though the one in Ahmedabad comprises four ten-floor buildings and the one in Navi Mumbai is a tower atop a parking podium. The coloured and dotted portions are the common facilities. The share of common areas in the built-up areas of the two buildings vary considerably. In Ahmedabad they take up 32.4 percent of the built-up area and in Navi Mumbai they take up 50 percent (see table below). A large portion of the additional area that has to be provided in Navi Mumbai is for parking.

Building regulations for vertical circulation, corridors and fire refuge areas are framed to ensure ease of vertical movement and safety in case of fire. They also impose mandatory costs that affect overall property costs. It is therefore important to conduct a cost benefit analysis when framing them.

Minimum parking requirements are meant to ensure that there is sufficient space within buildings for vehicles owned by people living in the buildings. The essay on parking in this newsletter explains why this is a problematic way of dealing with provision of parking. If we take the area that is not in common facilities as the habitable area, the study here shows that building bye-laws in Ahmedabad require construction of 24 sq. mts. of parking for every 100 sq. mts. of habitable space and in Navi Mumbai they require construction of 68 mts of parking for every 100 sq. mts. of habitable space.

More detailed research is needed to fully understand the impact of regulations. Comparative studies like this shed light on how building regulations that impose undue burdens and costs on both developers and consumers.

Avanish Pendharkar is Head, and Anju Pillai and Gaur Shelar are research interns at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Explained

Public Goods in Cities

Author: Bimal Patel

Street lighting, public safety and clean air are what economists refer to as ‘public goods’. These are both non-excludable and non-rivalrous (or non-depletable). They are non-excludable because, once provided, one cannot exclude individuals from enjoying their benefits. They are non-rivalrous, or non-depletable, because one person’s enjoyment of these goods does not diminish the amount available to others.

Street lighting, public safety and clean air satisfy both conditions, regardless of how many people benefit from them. They are, therefore, referred to as pure public goods. Impure public goods are those that meet these conditions only to some extent or sometimes. A street, for instance, provides full benefits to users until it becomes crowded. Once crowded, the benefits begin to diminish for everyone using it.

Typically, when public goods are provided by private actors or markets, they are under-supplied or inadequate. This makes the provision of public goods a major function of urban planning. Take street networks, for example. Private developers are perfectly willing to provide publicly accessible streets running through or along the edges of their properties. They are also willing to hand over ownership of these streets to local authorities to be integrated into a public network of interconnected streets. Indeed, this is how the cores of many old cities were formed. The figures below show examples of street networks formed in this way in the historical cores of Ahmedabad and Prague.

Street networks formed in this way are considered organic because they evolve incrementally and tend to follow original agricultural property lines. They are also non-hierarchical. While such networks are adequate for providing public access to individual properties and for meeting the needs of traffic within small neighbourhoods, they are inadequate for overall urban mobility.

Effective street networks require many wide arterial streets that stretch long distances, allowing people to cut through neighbourhoods and traverse long distances. However, private developers have no incentive to provide such arterial streets and so privately provided street networks tend to be inadequate. The provision of adequate street networks – a public good – requires planning intervention. It is therefore not surprising that the presence of a designed street network, such as those found in the ancient Greek city of Miletus and the Walled City of Jaipur (see figures below), is taken as evidence of the existence of urban planning.

Many elements and features of built environments that are central to well-functioning cities are public goods. They include: robust, efficient and safe street networks; adequate street lighting; generous parks and gardens; effective stormwater disposal and sewerage systems; clean air; and more. As public goods, they must be provided by the government through urban planning interventions. In fact, the provision of public goods may be considered the raison d'être of urban planning.

Though there is ample justification for the planned provision of public goods, doing so in practice is not always easy. This is because it is difficult to determine the appropriate level at which they should be provided, how they can be delivered efficiently, which public goods should be prioritised, which areas should receive attention, and how they should be managed once in place.

A higher level of public provision is not always better. Take streets and parks, for example. Broadly speaking, the more land devoted to them, the better it is for mobility and liveability. However, land in any area of a city is finite. The more land that is allocated to streets and parks, the less remains for buildings. In central city areas, inadequate availability of buildable land can drive up property costs and diminish overall well-being. In suburban areas allocating a large portion of land to streets is likely to be wasteful. Planners must use their judgement to strike a careful balance. This judgement must be informed by benchmarking, needs assessments, cost-benefit analysis, and cost-effectiveness studies and analyses. It must also be shaped by experience.

Public goods are paid for through taxes. Since the level of taxes that an economy can bear is limited, the amount of public goods that can be created through planning is also limited. Good planning requires finding ways to deliver public benefits without solely relying on tax revenues. For instance, using land pooling and reconstitution to create street networks in greenfield areas. Planners can also defer or phase the creation of public benefits. For example, they may initially focus on setting aside land for streets, and later – alongside economic growth and greater availability of tax revenues – pave the streets and provide infrastructure.

It is also not easy for planners to decide the priority in which to provide public goods or where they should be provided. What comes first: paved carriageways or paved footpaths? Which areas deserve investment first? There is no purely technical way to arrive at the right answer. Ultimately, these are political decisions and, therefore, planners must engage with the political process. In doing so, they can constructively serve the larger public good and ensure long-term well-being or become pawns of special interest groups.

Most urban public goods are not pure public goods. Streets, parks and sewage systems can easily become congested. When this happens, it is important to devise ways of limiting their overuse – often through pricing. Street use can be limited by introducing congestion pricing; the use of parks can be restricted by levying entry fees; and connections to sewage systems can also be priced. Each of these approaches poses its own technical, political and economic challenges.

Public goods are central to urban planning. Yet it remains challenging to determine the level up to which they should be provided, how they can be delivered efficiently, which public goods should be prioritised, which areas should be focused on, and how they should be managed after implementation. Planners must continually improve their ability to address these questions, because no city can be truly good without being generously endowed with public goods.

A good city is one in which even the poorest child can walk to a safe park, breathe clean air, and read in a public library. It is a city where the civic realm is a shared achievement. Public goods are how we materialise the idea that cities belong to all of us – not just as consumers, but as citizens. For everyone who calls the city home, public goods are a reminder that the best parts of urban life are those we share.

Bimal Patel is Chairperson of the Board at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Reading

How Hong Kong Became a Volumetric City

Author: Suyash Rai

Between 1950 and 2010, Hong Kong’s GDP per capita grew at an average annual rate of 4%, increasing more than elevenfold. Sustaining such growth over two consecutive generations is a rare achievement in human history. Most developed countries reached prosperity with 1.5–2% growth over much longer periods. The U.S., for example, took 146 years (1852–1998) to achieve Hong Kong’s six-decade increase. During this time, Hong Kong’s population also grew much faster than in most countries. Such prolonged, simultaneous economic and demographic growth is extremely rare.

Rapid economic growth generates resources, but rising population and incomes place increasing pressure on the built environment. Newcomers require floor space, infrastructure, and amenities, while higher incomes raise expectations for improved living conditions. When cities fail to adapt, the result is congestion, pollution, disease, slums, and a deteriorating quality of life.

As economies evolve, built spaces – from factories and offices to infrastructure – must keep pace with the changing forms of production. When the built environment lags behind the needs of producers and consumers, it becomes a barrier to growth. Institutions must therefore create an enabling framework before such challenges become overwhelming.

While Hong Kong has had its share of problems, it has arguably done a noteworthy job of evolving its built environment to meet the considerable challenges it has faced. Its success lies in how its built environment co-evolved with its growth, turning scarcity into ingenuity within a geographically constrained setting. In The Making of Hong Kong: From Vertical to Volumetric, Barrie Shelton, Justyna Karakiewicz and Thomas Kvan present a compelling account of how this happened. Urban planners, designers and city leaders may find in it valuable insight into how the built environment evolved through a continuous, adaptive process of negotiation and adjustment.

The authors argue that Hong Kong is not just vertical, but volumetric: a city that has evolved upwards, downwards, and laterally – across terrain, infrastructure, and podia-and-towers. Its layered spatiality – with elevated walkways, tunnels carved beneath mountains, and stacked ecosystems of shopping, transport and housing – emerged not from a singular planning vision but through incremental, mutually reinforcing decisions shaped by topography, infrastructure, population growth, and economic incentives. Hong Kong co-evolved its built environment to meet rising demands while building on only about a quarter of its total territory.

Beyond master planning and spontaneity

A major contribution of Shelton et al.'s work is to demonstrate that Hong Kong is neither a triumph of top-down planning nor an accident of laissez-faire urbanism. Rather, the city is the product of practical wisdom applied consistently over time – a cumulative and adaptive effort by institutions, planners, engineers and developers who responded to constraints and opportunities, negotiating the city into existence one decision at a time.

Shelton et al. suggest that Hong Kong’s built environment emerged from a dialogue between regulation, private initiative, architectural tradition, engineering possibility, spatial constraint and public need. Importantly, the absence of rigid zoning enabled hybrid forms to develop. Mixed-use podium-and-tower structures proliferated as responses to evolving social and economic demands – forms that simultaneously mediated traffic, enabled density, and sustained active street life.

The volumetric city: a new paradigm

The book’s key contribution is the concept of the volumetric city. Instead of organising space in two dimensions, Hong Kong learned to plan in three. Walkways float above roads; rail lines and pedestrian corridors tunnel through mountains and beneath towers; entire neighbourhoods rise on podiums, creating new ‘grounds’ above ground. This vertical layering and connective tissue generate extraordinary spatial efficiency and complexity. To outsiders it may feel labyrinthine – but for residents, the volumetric city functions efficiently.

Although Hong Kong’s administration resisted grand developmentalist schemes, it maintained a firm grip on land ownership. Long-term leases were used to channel private development in ways that supported public goals – most notably, the massive expansion of public housing and the co-location of transport infrastructure with dense development. It was also quite liberal in allowing connections across private plots, either by developing them directly or permitting private development of interconnections – on ground, well above the ground, and underground. This framework created incentives for private developers to build ambitiously, while also ensuring that growth occurred where infrastructure existed or could be efficiently supplied.

Hong Kong’s severe geographical limits forced vertical building. More importantly, as Shelton et al. show, it integrated verticality with connectivity – linking layers to enable movement, access and exchange. In many dense cities, vertical growth isolates; in Hong Kong, infrastructure and buildings are interdependent, not merely adjacent. Yet the authors caution that podium-and-tower developments have made parts of Hong Kong an ‘up-ended, concentrated version of suburbia’ – particularly in new towns and reclamation zones. Towers often become vertical cul-de-sacs, resembling low-density, horizontal garden city models such as Walter Bunning’s post-WWII.

Learning from constraints

A recurring theme in Shelton et al.’s account is that Hong Kong’s success emerged not despite its constraints but because of them. The city’s severe land limitations forced innovation in land use, building construction, infrastructure integration and regulations. For instance, the podium-tower typology, now ubiquitous in Hong Kong, began as a response to plot ratios and setback rules. Over time, it evolved into a versatile spatial form that allows for retail, transport, housing, and even civic functions to co-exist within a tightly packed volume.

Consider affordable housing for low-income households. The key question for supply-side policy is this: is it better than a slum? Ceteris paribus, this is what matters most to a slum dweller. The other important question is: what is its price? In a resource-constrained world, affordability is essential – regardless of who pays. These two questions are connected: setting quality standards detached from reality drives up costs. If government supplies the housing, rationing becomes inevitable due to limited resources; for market supply, such standards prevent affordable units from being built. Hong Kong wisely accepted minimal standards that were still better than the squatter settlements they replaced.

This offers a powerful lesson for rapidly urbanising cities, especially in the Global South. The goal is not to replicate Hong Kong’s form, but to adopt its logic of adaptation: allowing spatial experimentation while coordinating infrastructure. Institutions and planners must avoid paralysis from the pursuit of perfect foresight or the illusion that the future is knowable. They must learn from each decision and build iteratively.

Urban institutions as enablers

Shelton et al. avoid romanticising Hong Kong’s urbanism. They acknowledge its aesthetic monotony, weak street-level sociability, and social inequalities. Yet, they rightly argue that these do not outweigh the institutional and professional achievements that made the city work. Hong Kong succeeded where many others faltered: by aligning spatial innovation with infrastructure and consistent regulation. Its institutions acted as stewards, enabling wide-ranging physical improvisation while preserving coherence and functionality.

In this, the authors echo a core insight from Neil Monnery’s Architect of Prosperity, which credits Hong Kong’s take-off to a non-interventionist but enabling form of governance under Financial Secretary Sir John Cowperthwaite: the government’s role was not to dictate outcomes, but to shape incentives, maintain coherence, and enable cumulative problem-solving. Cowperthwaite’s ‘positive non-interventionism’ avoided over-planning while ensuring reliable provision of education, policing, port infrastructure and clean government.

When needed, it even extended to public housing to address crises such as the Shek Kip Mei fire. Their approach was not ideological but flexible, using interventionist tools when needed while allowing markets to flourish. On public housing – one of the most intrusive interventions – Cowperthwaite urged the state to build just enough to lower rents, indifferent to whether supply came from the public or private sector.

Three takeaways for Indian planners

1. Planning is about solving problems.

In rapidly growing cities, effective planning mainly means creating the conditions for solving problems in their context – by aligning regulations, infrastructure, land policy, and resource availability – rather than specifying outcomes. Planning is not about trying to create an imaginary city by design.

2. Function matters more than form.

No urban form should be fetishised; what matters is whether institutions adapt to pressures, coordinate across sectors, and guide the built environment’s evolution to serve the city’s needs. Ironically, this lesson comes from a territory long governed as a Crown Colony.

3. Three-dimensional thinking is critical.

Planning must extend beyond the surface, allowing underground and overhead spaces to be used for interconnection, and creating new ‘grounds’ for activity. Connectivity takes on a different meaning if one thinks three-dimensionally. In India, there is anxiety about private connections that cross public spaces – even though governments build such links. Hong Kong adopted a more liberal but regulated approach, allowing private transport solutions and connections between private structures that cross public spaces.

To be clear, Hong Kong's story does not lend itself to replication. Its colonial governance, centralised land regime, and economic circumstances were specific. But the deeper lesson is universally relevant: planning success lies in long-term institutional attentiveness, the capacity to adapt, and the humility to let the city grow wiser than its planners and rulers.

Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University