#5: Managing In-City Redevelopment | Measuring Redevelopment | Carrying Capacity | Constitutions and Cities

An essay on managing in-city redevelopment, an insight on measuring redevelopment, an explanation of carrying capacity, and a recommendation to read a book on the status of cities in constitutions.

Essay

Managing In-City Redevelopment

Author: Bimal Patel

Since India is urbanising and its population is growing, more and more people are living in its towns and cities. Urban Indians are also becoming more prosperous and demanding more floor space. This demand is being met by: the addition of buildings on the periphery of towns and cities, and the replacement of smaller buildings in long built-up areas with larger ones. Because of peripheral expansion, India’s towns and cities are expanding out, like ink blots, into the surrounding countryside. Due to redevelopment their cores are densifying and growing taller.

The previous issue’s essay proposed that well-managed peripheral expansion is expansion where, along with the spread of buildings out into the surrounding countryside, space is also being reserved for a robust network of streets, adequate gardens and essential amenities – about 30–40% of the expansion area. Streets can be paved later, infrastructure lines can be laid later, gardens can be developed later, and amenities can be provided later – but creating space for these purposes by appropriating land after an area has been built up is practically impossible.

The essay on peripheral expansion also suggested that central and state governments should focus on monitoring how much land on the periphery of cities planning authorities have been able to convert from ‘agricultural’ to ‘urban’ – that is, from organic layouts of farms and cart tracks to formal layouts with public streets, gardens, amenities, and buildable plots. In areas opened up for expansion, they should also track whether authorities have designated a sufficient proportion of land for public use, and whether they have actually appropriated it.

In this essay, I propose something similar for in-city redevelopment. Well-managed redevelopment of built-up areas is redevelopment that ensures that, along with the replacement of smaller buildings with larger ones, street networks are also improved – at the very least. Why is it important for in-city redevelopment to be accompanied by the improvement of street networks? What about street networks needs improving and why? How can this be accomplished in the Indian context?

Streets are the arteries that make cities functional. They are meant to accommodate a vast array of activities and elements, such as: motorised and non-motorised traffic; pedestrians; vendors; parking; loading and off-loading of goods; utility lines for water, sewage, stormwater, electricity, and communications; trees; light poles; bus stands; signage; and street furniture. When small buildings in an area are replaced by larger ones with more floor space and more people, the stress on the area’s street network also grows. If the street network is not adequate to withstand this additional pressure, it becomes imperative to improve it.

Street networks in almost all Indian cities are weak. They are barely adequate for handling existing loads, and in-city redevelopment is increasing that load. For in-city redevelopment to be beneficial and sustainable, it is imperative that planning authorities ensure street networks are also improved. Failing this, redevelopment will increase congestion, impede mobility, and hinder urban productivity.

Let me hasten to add that the current low capacity of Indian street networks should not be taken as a reason to stall redevelopment. Indian cities have much to gain from redevelopment and densification. However, it would be far more beneficial if redevelopment were accompanied by the improvement of street networks.

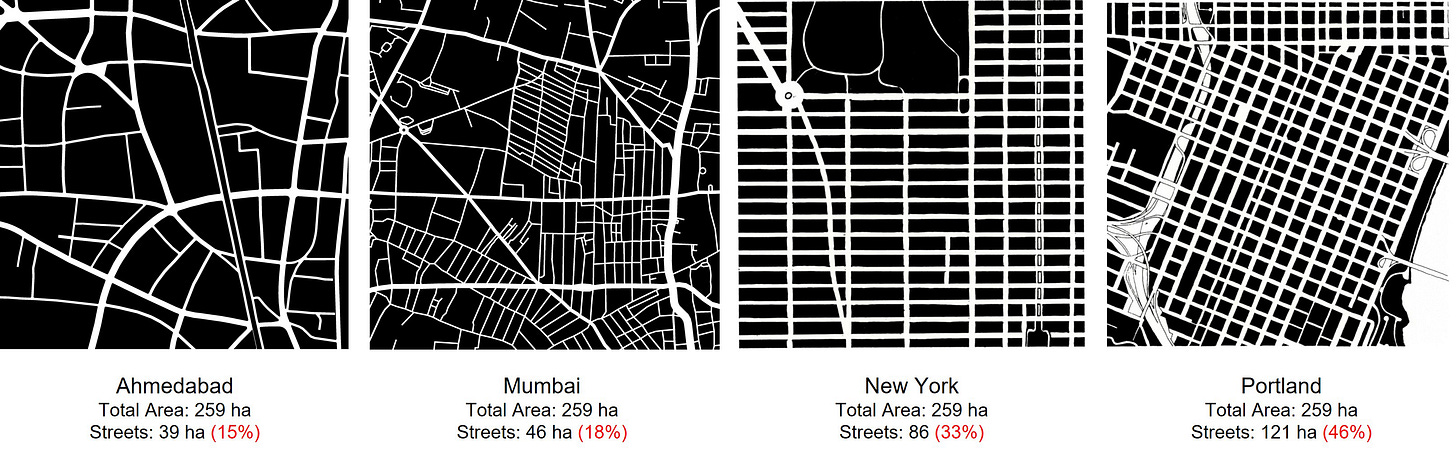

Street networks in urban India are characterised by two deficiencies. First, the proportion of land devoted to streets is very low – ranging from just 15–20%. There simply isn’t enough space for all the activities and functions that streets must accommodate. Second, Indian street networks tend to have branching structures. Because of this anyone who wants to cross from one area of a city to another has to use the network’s trunk routes, making them vulnerable to congestion.

In contrast to Indian cities, the proportion of land devoted to streets in well-functioning cities worldwide is much higher. Street networks in these cities usually have grid or lattice structures. This is illustrated in the figure below, which shows street networks in the central areas of Ahmedabad, Mumbai, New York, and Portland. Most well-functioning cities, in their central areas, devote anywhere from 25–35% of their land to streets. Their networks are also dense grids rather than branching structures. This means that they have a higher total length of streets, more nodes, and smaller block sizes. Improving street networks therefore means, simultaneously, increasing the proportion of land devoted to streets and converting branching structures into efficient grid structures. This can be done by widening existing streets and adding new ones in a way that increases the total length of streets, increases the number of nodes, and reduces block sizes.

Good street networks require much more than just adequate space and grid structures. For streets to work well, they must be carefully designed, properly paved, and equipped with robust infrastructure. If necessary, their traffic carrying capacity needs to be augmented by the provision of mass transport facilities like buses and trams. However, all of this can only be done if there is sufficient space, and the structure of the network is workable. Therefore, it is important for planners to prioritise street network improvements by expanding street space and improving networks characteristics.

Can street networks in already built-up areas of Indian cities ever be improved? The answer to this question is yes. This is primarily because, on account of the peculiar suburban morphology of Indian cities, there is a lot of unutilised land that can be used to improve street networks. Land use in Indian cities is distributed as follows: 15–20% of the land is used for streets; of the remaining, less than 5% is devoted to parks; about 25% is covered by buildings; and, most importantly, about 50% is in the form of open land around buildings within private compounds. It is open because onerous building regulations statutorily require landowners to leave it open as setbacks and other types of open spaces. Most of this land is fragmented into thin slivers and small patches that cannot be well-used. The challenge is to bring this land into the public domain and use it to strengthen street networks. This is what planning for in-city redevelopment should focus on.

Planned and systematic appropriation of private land to improve street networks requires a statutory planning mechanism akin to the land pooling and reconstitution mechanism for peripheral expansion. As discussed in the previous issue, this mechanism, developed in the early twentieth century, was used by planners to make town planning schemes to tackle the problem of peripheral expansion. The mechanism worked and continues to do so because it was based on sound principles. It respected private property rights and, therefore, appropriated land without relying on forceful land acquisition. It valued fairness and did not dispossess a few to create benefits for the many. It worked with the market instead of against it. It appropriated a portion of increments in land value – caused by planning improvements – to pay for the costs of improvements. As a result, it was costless for authorities. It allowed landowners to retain at least half of the increments caused by planning improvements, helping planners co-opt landowners in the planning process. It enabled planners to make detailed plans that took account of minute features of the planning area. If Indian planners want to tackle the problem posed by in-city redevelopment effectively, they must develop a planning mechanism based on these principles.

The Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) developed a statutory planning mechanism of this type along with a plan for the centre of Ahmedabad which is shown in the figure below. It was backed by amendments to the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act in 2014 and 2017 and is currently under refinement. It envisaged the management of in-city redevelopment as follows.

The Local Area Plan for the 1.25 sq km Central Business District of Ahmedabad increased the proportion of land devoted to streets from 22% to 40%.

Planning authorities designate an area as a redevelopment area and increase Floor Space Index (FSI) within it to incentivise the replacement of small buildings with larger ones. In tandem with this, they prepare a Local Area Plan (LAP) to regulate redevelopment, levy floor space-based development charges, appropriate land to improve the street network and undertake capital investments. LAPs are prepared in the following manner.

1) The redevelopment area is surveyed in detail. Precise maps showing buildings, property boundaries, streets, pavements, trees and infrastructure are prepared.

2) Proposals for widening existing streets and adding new ones are carefully drawn up with two objectives in mind: increasing the proportion of land devoted to streets and improving network characteristics by increasing the total length of streets, increasing the number of nodes, and reducing block sizes. As far as possible, streets are widened only up to the extent of front setbacks, and new streets are positioned so that they straddle the boundaries of adjacent plots and only extend up to the extent of side setbacks.

3) Setbacks from boundaries between adjacent plots are carefully drawn up. These setbacks must be left open and are intended to ensure that sufficient space is available for the movement of fire tenders and other emergency vehicles. Care is taken to minimise the amount of land thus rendered unbuildable.

4) After street widenings, new streets and setbacks have been demarcated, the remaining portions of original plots are demarcated as areas that can be built upon.

5) The areas of all original plots, appropriations from each of them and their residual portions are tabulated. Floor space development rights (FSI rights) of the appropriations are transferred to the residual plots. This, in effect, allows land to be appropriated without appropriating its development potential and therefore its financial value. However, land is appropriated only when plots are redeveloped. Bit by bit, as redevelopment progresses in an area, its street network is also strengthened.

Local Area Plans are long-term strategic plans that are meant to be realised gradually. Three features make them practically workable. First, the fact that land is appropriated only when plots are redeveloped makes Local Area Plans non-threatening to plot owners who are not looking to redevelop their plots and who do not want their lives to be disrupted. Second, the fact that land is appropriated but its development potential is not, makes the appropriation painless for plot owners. They get to retain the financial value of their plots. Third, the fact that authorities do not have to compensate landowners makes it possible for them to appropriate land without incurring any cost. It also eliminates the contentious problem of having to fix a value for the appropriated land.

Ensuring sustainable in-city redevelopment will require development of practically workable planning mechanisms like the Local Area Planning mechanism described above. This is what central and state governments should focus on first. Once planned redevelopment is underway, they should monitor progress by tracking the extent of redevelopment plans that have been put in place and the amount of land that has actually been appropriated for strengthening street networks. Without this, the rapid redevelopment that India’s towns and cities are witnessing is more likely to harm them than improve them.

Bimal Patel is Chairperson of the Board, CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Insight

Quantifying Redevelopment in Ahmedabad

Authors: Prachi Merchant and Prajwal Parmar

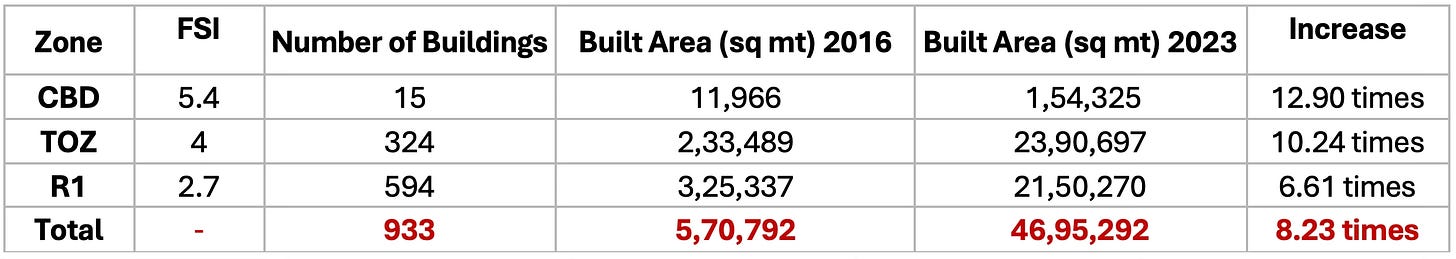

CBD: Central Business District along Ashram Road

TOZ: Transit-oriented zone along Metro and BRTS corridor

R1: Residential zone

In this article, we describe a novel method to map and quantify redevelopment and apply it to Ahmedabad. The Open Buildings 2.5D dataset allows us to analyse the changes in building height over a seven-year period from 2016–2023. The dataset has an accuracy of 82% and was further validated using temporal Google Earth imagery.

Using this dataset, we have extracted the buildings that have undergone redevelopment and measured changes in the built area for those buildings. We did this exercise in the following steps:

1) We identified the building footprints in 2016 and 2023.

2) We removed all buildings that were built on plots that had been vacant in 2016.

3) For the remaining building, we applied filters to identify the buildings that have increased their footprint area and/or have grown by more than two floors between 2016 and 2023.

4) Using Google Earth Imagery, we reviewed the time lapse for individual buildings for final validation.

5) For the buildings that remained after the validation, we then measured the built-up area in 2016 and 2023 and calculated the difference.

6) We then overlaid the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) Development Plan layers – mainly Central business district (CBD), Transit-oriented zone (TOZ) and R1 – to carry out zonal analysis. This allowed us to identify the areas where redevelopment is evident and how the FSI provisions provided may have been an important factor for redevelopment in the city.

The above chart and map show the quantity, area, and location of buildings that have been redeveloped in Ahmedabad from 2016 to 2023. It is observed that maximum redevelopment has occurred in the western side of the city. Redevelopment has taken place along TOD (Transit-Oriented Development) corridors and arterial roads in the R1 zone, and in the CBD area. Following are the findings from this exercise:

First, Ahmedabad has witnessed 0.45% redevelopment within this time frame; this is mainly plot-wise redevelopment and has resulted in increased floor space on the same plots.

Second, the CBD zone allows special provision for FSI up to 5.4 under the Local Area Plan (LAP) mechanism, allowing higher floor area consumption. TOZ is an overlay zone allowing FSI up to 4 and promoting TOD with provisions for high-density development along the corridors. Residential zone (R1) allows a maximum permissible FSI of 2.7 covering areas with high potential for redevelopment. All these provisions of higher FSI were made to incentivise redevelopment in the city.

The method used here can help monitor overall city redevelopment.

Prachi Merchant is Deputy Head and Prajwal Parmar is a Research Associate at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Explained

Carrying Capacity

Author: Suyash Rai

Recently, a non-profit organisation filed a public interest litigation in the Bombay High Court that requested the High Court to issue directions to have a comprehensive carrying capacity study of Mumbai conducted, and to ensure that the findings of the study are incorporated into future town planning policies, so that implementation is kept within the limits of the carrying capacity. As a concept, carrying capacity has had a long shelf life. It keeps making a comeback.

Carrying capacity traditionally refers to the maximum population or level of activity an environment can sustain without degradation. In classical ecological thinking, it is treated as an exogenous constraint – defined by the availability of land, water, food and energy. This framing implies a fixed, natural limit independent of behaviour. However, when applied to human societies, this view is limited. Carrying capacity is not a passive environmental boundary; it is endogenously shaped by human action through technology, institutions and social norms.

Humans differ from other species. We transform, rather than merely adapt to, our environment. Through innovation, planning and cultural change, societies alter the very conditions that determine their capacity to support populations. Carrying capacity, then, becomes a dynamically evolving threshold rather than a natural ceiling.

A significant way humans shape carrying capacity is by transforming production. Early agriculture expanded the food base through domestication, irrigation and soil management. The Green Revolution further pushed boundaries with synthetic inputs and high-yield crops. The Industrial Revolution enabled the most dramatic leap in carrying capacity. Mass production, transport, tall buildings, and urban growth supported rising populations and standards of living. Technological advances such as renewable energy and desalination continue to stretch ecological limits. However, these developments are not automatic; they depend on investments, institutional support and social priorities. Carrying capacity is not what nature offers, but what society can sustainably extract and regenerate, and how efficiently it can be put to use.

Institutions – formal and informal rules and governance systems – mediate carrying capacity. Two societies with similar ecological endowments may differ greatly in their outcomes, depending on how they manage resources. Effective institutions foster collective action, regulate use, and encourage conservation. As Elinor Ostrom’s work shows, communities can design governance systems to manage commons sustainably. In contrast, weak institutions invite overuse and degradation, reducing a society’s effective carrying capacity.

Consumption patterns and cultural norms play a further role. What societies define as a ‘good life’, and how they distribute resources, influences demand on the environment. High-consumption lifestyles can place greater strain on ecological systems than those oriented towards sufficiency and equity. Cultural attitudes towards waste, status and nature shape these patterns. Education, public discourse and civic movements can shift norms over time, affecting how much pressure human behaviour places on ecological systems.

Urban planners, in particular, play a significant role in shaping the carrying capacity of cities. When a city’s economy grows, markets help expand its carrying capacity by responding to the demand for more floor space, services and amenities. However, markets have limitations. They may not supply adequate public spaces, mobility systems and utilities. Moreover, unfettered growth is likely to be accompanied by congestion, pollution, and public health problems.

Planning can complement markets by helping overcome these limitations. It also involves regulation of market activities to ensure that private actions do not negatively impact others. As Alain Bertaud argues in his book Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, planning can play a key role in improving mobility and affordability. A city’s carrying capacity fundamentally depends on these two features of its built environment. So, planners can influence how many people a city can support – and at what level of well-being. A corollary of this is that planners can also limit urban carrying capacity through arbitrary restrictions, poor mobility systems, and overly rigid regulations. Finding the right balance between markets and planning can ensure that a city’s carrying capacity grows at a rate that meets the demands being signalled by the people, many of whom are not yet in the city but want to live there.

In conclusion, carrying capacity should be understood as a social-ecological construct. It is shaped by how societies produce, govern, consume, and imagine the future. Rather than a fixed boundary, it is an evolving frontier – subject to human intention and capacity. The challenge is not just to live within limits, but to recognise that we shape those limits ourselves. Carrying capacity is not destiny – it is a choice.

Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University

Reading

Cities in Constitutions

Author: Suyash Rai

With global urbanisation accelerating – especially in the Global South – and megacities becoming dominant economic and demographic centres, there is a need to give them a proper place in the constitutional scheme. City, State: Constitutionalism and the Megacity by Ran Hirschl (Oxford University Press, 2020) is a landmark study at the intersection of constitutional law and urban governance that makes exactly this argument. Hirschl’s core argument is that constitutional law has failed to keep pace with the growth of cities. He identifies a ‘constitutional blind spot’ regarding cities, arguing that legal frameworks largely ignore their growing importance, leaving them politically and administratively disempowered.

The book convincingly claims that constitutions remain fundamentally state-centric, structured around the priorities of national and subnational (e.g. state-level) governments. Cities – despite housing over half of the global population and expected to accommodate 75% by 2050 – are rarely granted meaningful constitutional standing. This legal invisibility, Hirschl contends, hampers their ability to address urgent challenges such as inequality, climate change, housing shortages, and democratic underrepresentation.

Structured in six chapters, the book methodically outlines the marginal role of cities in constitutional discourse. Hirschl begins by tracing this omission to historical legal traditions, particularly in the Global North, which evolved under a centralised, state-focused logic. Constitutions in countries such as the United States, Canada, and the UK often place cities under tight control by higher tiers of government. The book then pivots to examine the Global South, where, due to rapid urbanisation and unique socio-political dynamics, some countries have adopted more progressive constitutional frameworks. South Africa and Brazil, for instance, embed metropolitan autonomy into their constitutional designs, giving cities a stronger legal and political footing.

Yet even within the Global South, urban constitutionalism is inconsistent. Hirschl’s analysis of India exemplifies the ambivalence. Although the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, introduced in 1992, aimed to strengthen urban local bodies, it fell short of granting true autonomy. The case of Delhi – a megacity with partial statehood – illustrates this tension vividly. While Delhi has an elected government, its real powers are constrained, and it must rely on the central government for many things. A similar lack of autonomy afflicts Mumbai, where the municipal corporation (BMC) remains subordinate to state authorities, hindering its capacity to pursue large-scale urban development projects.

Hirschl argues that such arrangements are inadequate for the scale and complexity of modern urban governance. Cities are not just large towns; they are political, economic and cultural entities requiring commensurate legal recognition. Their current subordinate status means they are often underfunded, poorly represented in national decision-making, and unable to implement policies tailored to local needs.

The book's comparative approach is one of its greatest strengths. By examining diverse cities – Toronto, London, Hong Kong, Mexico City – Hirschl highlights both the variety of legal treatments cities receive and the consequences of constitutional design choices. Cities in federal systems often fare worse, as their powers are not constitutionally guaranteed and are instead delegated by states or provinces. In contrast, places like Johannesburg benefit from explicit constitutional guarantees of metropolitan autonomy, allowing for more responsive and innovative governance.

Urban inequality is a recurring theme in the book. Hirschl emphasises how constitutional marginalisation contributes to socio-economic disparities. Cities generate wealth and innovation, but their populations – especially the urban poor – frequently lack access to basic services. He links this to structural issues in governance: when cities cannot raise their own revenue, plan independently, or manage infrastructure projects, they remain reliant on higher levels of government, which may not prioritise urban needs.

The book also explores representational injustice. Rural areas often enjoy disproportionate political power relative to their population or economic contribution – a phenomenon visible in many democracies. This skews policy outcomes and resource allocation, further marginalising urban centres. Hirschl’s critique is not just legal but also normative: he believes that the failure to empower cities undermines the principles of democratic representation and responsive governance.

In response, Hirschl proposes a bold rethinking of constitutionalism. He advocates incorporating cities directly into constitutional frameworks through urban charters, metropolitan clauses, and the principle of subsidiarity – the idea that governance should be exercised at the most local level possible, unless greater scale is necessary. These reforms, he argues, would empower cities to act decisively on issues that matter to them and align constitutional design with demographic and economic realities.

For urban planners and designers, City, State offers both diagnosis and direction. Most planning professionals operate within pre-existing legal and political frameworks, often without questioning their constitutional basis. Hirschl’s work challenges this – calling on planners to become more aware of the institutional constraints that shape their work, and to advocate for reforms. By showing how constitutional design influences everyday governance outcomes, the book helps bridge the often siloed worlds of law and planning.

India provides a particularly relevant case study. With its large and growing urban population, it exemplifies both the promise and pitfalls of megacity governance. India could learn from constitutional innovations in places where cities have more control over their finances, land use and service delivery. Applying these lessons would require both legal reform and political will, but the potential payoff - more accountable and capable urban governance – could be significant.

Another valuable contribution of the book is its attention to urban creativity in the face of legal constraints. Hirschl highlights cases where cities have pursued de facto autonomy through innovation: forming public-private partnerships, leveraging international networks, or building coalitions with civil society actors. These examples underscore the agency of urban actors and point towards practical avenues for reform, even when constitutional change is slow.

Nonetheless, City, State is not without limitations. Hirschl avoids offering a precise definition of ‘city’ as a constitutional entity. He gestures towards features like density and diversity but stops short of systematically distinguishing cities from other forms of local government. This conceptual ambiguity may hinder efforts to translate his proposals into policy or law. Additionally, while the book’s focus on megacities is justified by their scale and influence, it underrepresents the diverse experiences of smaller cities and towns, which face distinct challenges. A more inclusive framework might have broadened the book’s relevance.

Minor caveats aside, City, State is a pioneering contribution to the field. Its combination of legal theory, comparative analysis and policy relevance makes it essential reading for scholars, policymakers and urban practitioners alike. Hirschl’s call to reimagine constitutionalism in the age of urbanisation is both urgent and inspiring. For urban planners, the book is a reminder that the most innovative designs or efficient plans can be thwarted by structural constraints – and that true transformation may require engaging with constitutional politics.

Ultimately, City, State is a call to action: to move beyond treating cities as administrative conveniences or policy arenas, and to recognise them as political entities deserving of constitutional respect and empowerment. For those working on the front lines of urban planning and governance – especially in complex, contested, and rapidly growing cities – Hirschl provides a framework to think bigger, deeper, and more structurally about what it means to build better cities.

Suyash Rai is Chair of Research at CUPDF, a Centre of Excellence at CEPT University