#4: Managing City Expansion | Measuring Urban Sprawl | Spatial Economy

An essay on ways of managing peripheral expansion of cities, an insight on measuring urban sprawl, and a recommendation to read a landmark book on the theory of spatial economics.

Essay

Managing Peripheral Expansion

Author: Bimal Patel

Indian urban planners should prioritise better management of peripheral urban expansion and urban redevelopment. Nothing is more important at this stage of the country’s urban development. What ‘well-managed peripheral expansion and redevelopment’ means needs a clear and objectively measurable definition. Managing both also requires effective planning methods. This essay focuses on peripheral expansion; the essay in the next issue will address the challenge posed by redevelopment.

India is urbanising. Its population is also increasing, and so more and more people are living in India’s towns and cities. Urban Indians are also becoming more prosperous, and their consumption of everything is expanding – including floor space. Rapidly rising demand for floor space in urban areas is being met by the addition of buildings on the periphery of towns and cities, and by the replacement of small buildings with larger ones in already built-up areas. Like inkblots, India’s towns and cities are expanding into the surrounding countryside, at the same time as their central cores densify and grow taller.

At this stage of urban development, ensuring that peripheral expansion and in-city redevelopment are well-managed is the primary and most urgent challenge facing Indian urban planning. Planning authorities must first demonstrate their ability to tackle this challenge. Without a basic capacity to manage urban growth, it makes little sense to tackle other more sophisticated objectives. Such an assertion begs the question: what does ‘well-managed’ mean, and how can peripheral expansion and in-city redevelopment be well-managed in the Indian context?

I would like to propose a very simple definition of ‘well-managed peripheral expansion’. It simply means a manner of expansion such that, along with the construction of new buildings on the periphery, land is set aside for a robust and orderly network of streets, and for public parks, gardens and amenities. Streets can be paved later, utilities such as water supply and sewerage can be provided later, transport systems can be built later, and parks, gardens and amenities can be developed later but, once an area is developed, it is very difficult – or practically impossible – to appropriate land for streets, parks and gardens.

The most liveable, efficient and productive cities of the world are so today because, when they expanded into their peripheries, they set land aside for streets, parks and gardens. Cities that expand haphazardly out into their peripheries, without providing for good street networks and ample open spaces, are impossible to upgrade later, despite authorities wanting to do so and having the resources to widen or add streets or provide parks.

Managing peripheral expansion is a difficult urban planning challenge. This is because peripheries of most Indian towns and cities are agricultural landscapes. They have an organic layout of closely packed, irregularly shaped, variously sized and privately owned farms. Most farms have no direct access – they can only be reached by twisting cart tracks and by crossing neighbouring farms. Converting such landscapes into urban layouts requires reshaping farms into regularly shaped plots and providing streets that are wide enough for vehicular traffic, pedestrians, infrastructure and the many other functions that urban streets serve. Urban layouts also require publicly owned land for parks, gardens and social amenities.

Conversion of agricultural areas into urban areas is not only a matter of being able to design new urban layouts and physically transform the existing landscape. It requires land for public streets, parks and amenities. In a good urban layout, almost 35–40 percent of the land area must be devoted to public facilities and amenities. This is not a trivial matter. Therefore, the real challenge in managing peripheral expansion is one of appropriating private land to create public benefits.

Ideally, urban planning authorities should be able to convert large amounts of agricultural land into urban layouts, with robust street networks and sumptuous plots of land for parks and amenities, well before towns and cities start spreading out into their peripheries. Their success should be measured by the amount of such land – ready to accommodate peripheral growth – they have been able to supply to the market. Unfortunately, much remains to be done on this front. Today, authorities deal with peripheral expansion in five different ways.

Laissez-faire expansion

A large proportion of India’s towns and cities are growing out into their peripheries in a haphazard, laissez-faire manner with planning authorities playing a minimal, post-facto role and markets playing an overarching role. Such disorderly growth is evident in satellite images of peripheries of many cities, such as Chandigarh, Nagpur, Calcutta, Pune and Lucknow. When towns and cities grow in a laissez-faire manner, the expansion of urban areas and street networks takes place in an organic, piecemeal way. Usually, farms along roads radiating out into the surrounding countryside are built on first. The growth then spreads and thickens, with street networks also branching out organically, like veins and arteries.

In many cases, planning authorities simply look the other way when such growth is taking place. Later, they attempt to upgrade these areas by paving streets and providing infrastructure. Naturally, there are severe limits to the extent to which areas that have grown organically can be upgraded. In some cases, planning authorities play a slightly more proactive role. They draw up a set of rules that allow landowners or developers to convert individual farms to urban uses, require them to create streets within their developments, and stipulate that these streets be turned over for public use. They also levy development charges to fund the later provision of public utilities. Then, slowly, as developer after developer converts individual farms to urban uses, these individually provided streets begin to connect and form a network.

Street networks that emerge organically are unlikely to be orderly or functionally robust. They tend to have a branching structure with narrow, twisting streets. Such street networks, lacking wide and well-aligned arterial streets, are not very suitable for clearing through traffic and for laying unimpeded trunk lines for utilities. Urban areas that have grown in a laissez-faire manner also tend to lack parks and gardens. In addition, such areas usually have a spread of small, low-rise buildings. Adequate as these areas may be to immediate expansion needs, they are difficult to redevelop and upgrade later with better street networks and larger buildings.

This is why laissez-faire expansion locks cities into low-density development, forces them to expand far more than necessary, and results in them spending considerably more on infrastructure and transport in the long run.

Master plans and laissez-faire expansion

One way in which planning authorities attempt to improve upon laissez-faire expansion is by using master plans to provide arterial street networks and public amenities. In this approach, authorities first draw up a city-wide master plan that demarcates areas for peripheral expansion, arterial streets, and plots for public parks, gardens and amenities. The land demarcated for streets, parks and amenities is ‘reserved’ for acquisition and later appropriated using the land acquisition mechanism. The remaining land, not reserved for public use, is allowed to be urbanised in a more or less laissez-faire manner, as described above.

While this method of managing peripheral expansion is intended as an improvement on laissez-faire expansion, in practice, it has proven very challenging to implement masterplans, largely because it is very difficult for authorities to acquire land reserved for streets and amenities in a timely manner. Acquisition is usually delayed by a lack of funds, legal challenges mounted by those whose land has been demarcated for acquisition, and political interventions prompted by complaints from those who stand to lose their land to reservation. Often, the land ‘condemned by reservation’ is encroached upon by slums, with the connivance of landowners. In general, most authorities across India have not been able to acquire much of the land demarcated by them for streets and only negligible amounts for amenities.

Areas that emerge from master plan and laissez-faire expansion, though they are better served by a few arterial streets, are also, like areas that have emerged purely from laissez-faire growth, difficult to upgrade later. They lock cities into a low-density and inefficient future. In addition, this method, because of the discretion that planners enjoy in reserving land for forceful acquisition, places vast powers in the hands of planners and government officers involved in the planning process. This power can be easily abused.

Expansion through large-scale land acquisition

This method has been used for both establishing new towns and for managing the expansion of existing ones. In this approach, authorities first demarcate vast tracts of agricultural land for developing new towns or for urban expansion. This land is then forcefully acquired from farmers using powers of eminent domain. Planners then draw up urban layouts with streets, amenities and individual building plots. This is followed by the development of streets and other infrastructure, and sale or allocation of developed plots to users.

In this system, the authority essentially acts as a large-scale land developer with powers of eminent domain. Chandigarh and Bhubaneshwar were among the early new towns developed in this manner. The expansion of New Delhi envisioned in the Delhi Master Plan of 1962 was also effected in this manner. Around 250 square kilometres of agricultural land was acquired by the Delhi Development Authority.

This manner of managing urban expansion provides a blank slate and, therefore, considerable freedom for planners to design efficient urban layouts. However, it has many downsides. Authorities require vast resources to meet the cost of land acquisition and infrastructure development. They also require sophisticated implementation capacities to manage large-scale land development. The success of large-scale land acquisition is also dependent on landowners in the periphery of cities being pliant, and on authorities being able to offer manageable levels of compensation. This was the case when vast tracts of land were acquired in, for example, Delhi, Gandhinagar and Navi Mumbai. However, this is no longer the case in most towns and cities, with farmers being highly politicised and no longer willing to let their land be acquired at throwaway prices.

Expansion through private township developments

In this method of managing peripheral expansion, instead of acquiring large tracts of land themselves, authorities rely on private developers to purchase agricultural land from farmers in the periphery of cities. Then, under special ‘township’ policies, they zone the land for urban development in exchange for: development fees, the designation of certain streets as public rights of way, and some amenities being made available for public use. They also set building regulations that developers must adhere to and, in some cases, provide road connectivity.

At one level, this method is similar to laissez-faire expansion. The difference between the two is that tracts of land, to be eligible for rezoning under township policies, have to be of a certain minimum size, which is usually quite large.

Township policies essentially support large-scale developers to purchase land at agricultural land prices and benefit from the increase in land value resulting from formal rezoning of the land. Their success depends on farmers being unaware of how much developers are likely to benefit after acquiring their farms. This raises questions of fairness and whether the state should use planning powers in this way. It also explains why the method is unlikely to work once farmers on the periphery have wised up and begin demanding higher prices.

In addition, the effectiveness of township policies depends on developers being able to purchase contiguous farms and assemble large tracts of land. Their efforts can easily be thwarted by holdouts – farmers who refuse to sell and force developers to build around their properties. For both of these reasons, township policies offer limited value in managing urban expansion.

Land pooling and reconstitution

This method of managing urban expansion was devised in 1915 and used extensively to manage the expansion of towns and cities in the Bombay Presidency – for example, Bombay, Ahmedabad and Poona. It has remained in more or less continuous use in Gujarat. Here, authorities demarcate tracts of agricultural land for conversion to urban layouts. They then survey the area in detail and record the extent and value of all the farms within the tract.

Once this is done, the entire area is treated like a blank slate. This is what is meant by ‘land pooling’. Planners then draw a new layout for the area, showing streets, parks, other amenities and properly shaped building plots. This is referred to as ‘land reconstitution’.

The building plots in the new urban layout all correspond to the farms in the original layout. Their size, however, is reduced by the same proportion as the area of all the land used for creating public facilities to the total area of all the farms. This ensures that everyone contributes an equal proportion of their land towards the creation of public facilities and amenities.

Having reconstituted the land, planners first determine the amount of compensation due to each landowner for the land contributed for public use. Compensation takes into account both the area of land lost and its original value.

Next, the planners undertake a valuation of each new building plot to estimate the increment in land value resulting from the conversion of farmland into a building plot in the urban layout. This estimation takes into account various features of the new plot, such as its location in the layout and the street frontage it enjoys.

A betterment charge – amounting to half of the increment in land value – is levied on the plot owner. Owners are also charged for the cost of building infrastructure in the area, in proportion to their land holding in the total area of the layout. Finally, the new layout is sanctioned as the new cadastral layout of the area.

This method has a number of merits. It is self-financing and does not require authorities to invest money in acquiring land or building infrastructure. It is based on principles of fairness and does not dispossess a few to create benefits for all. It also allows farmers to benefit from future increments in land value. It allows almost as much freedom as large-scale land acquisition in designing urban layouts.

However, this method is also difficult to institutionalise. In addition to needing the requisite legal and administrative framework, it requires planners who know the art of using their powers to reconstitute and value land to negotiate with individual landowners, address their grievances and develop meaningful urban layouts. They must adopt an attitude that respects property rights and sees the role of the state as that of a facilitator.

It is not easy to institute the land pooling and land reconstitution mechanism. However, where it has been institutionalised, which is currently the case only in Gujarat, it works very well. Authorities are able to convert vast amounts of agricultural land into urban layouts well before development begins, ensuring orderly peripheral expansion.

Managing peripheral expansion

At this stage of India’s urban development, the most important and urgent challenge facing Indian urban planning is managing urban growth. Once towns and cities have expanded into their peripheries, it becomes extremely difficult to change the basic structure of their street networks or to appropriate land for parks and gardens. It is therefore imperative for planners to build capacity to manage peripheral expansion in a way that ensures that space is set aside for an orderly and robust network of streets, as well as for parks.

One can be agnostic about the specific method planning authorities adopt to manage peripheral expansion. However, the importance of effectively managing this process should not be underestimated. In view of this, the key statistic that central and state governments should be collating and publishing is the amount of agricultural land on the periphery of cities that authorities have been able to annually convert into urban layouts with robust street networks, sumptuous plots for parks and amenities, and a supply of buildable plots that the market can easily use to meet the growing demand for floor space.

Insight

Peripheral Growth in Cities of Gujarat

Authors: Mohit Kapoor, Prajwal Parmar

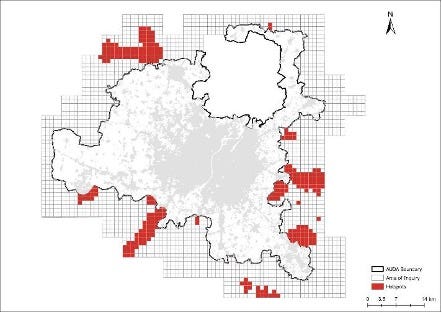

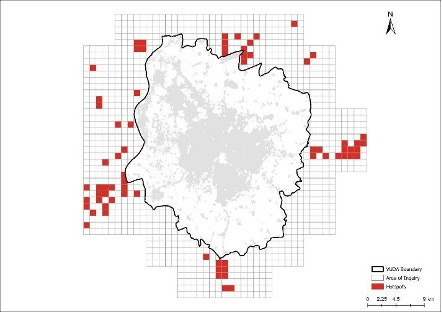

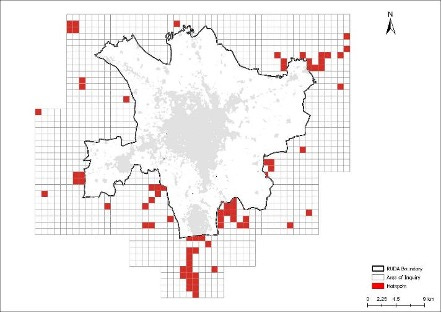

The figures below show hotspots of urban growth on the outskirts of the planning boundaries of four major cities in Gujarat: Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Surat, and Rajkot. The unplanned growth outside the planning boundaries of all four cities was measured by creating a series of 1 km x 1 km grid. This zone was considered as ‘Area of Inquiry’. Hotspots were derived using the Getis-Ord Gi statistic, which identifies statistically significant areas of dense built-up development based on the spatial context of surrounding grid cells. In this context, 'built-up' encompasses buildings, roads, pavements, and other impervious surfaces. The analysis utilized ESRI’s 10-meter resolution Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) data, derived from Sentinel-2 imagery, for the years 2018 and 2023. The maps below highlight areas that experienced rapid built-up growth in the ‘Area of Inquiry’ during this period.

Ahmedabad

Vadodara

Surat

Rajkot

Ahmedabad's growth hotspots are concentrated in the northwest, southwest, and east. In Surat, they are primarily in the north and east, constrained by the coastline to the west. Vadodara and Rajkot show a more scattered distribution of hotspots in all directions.

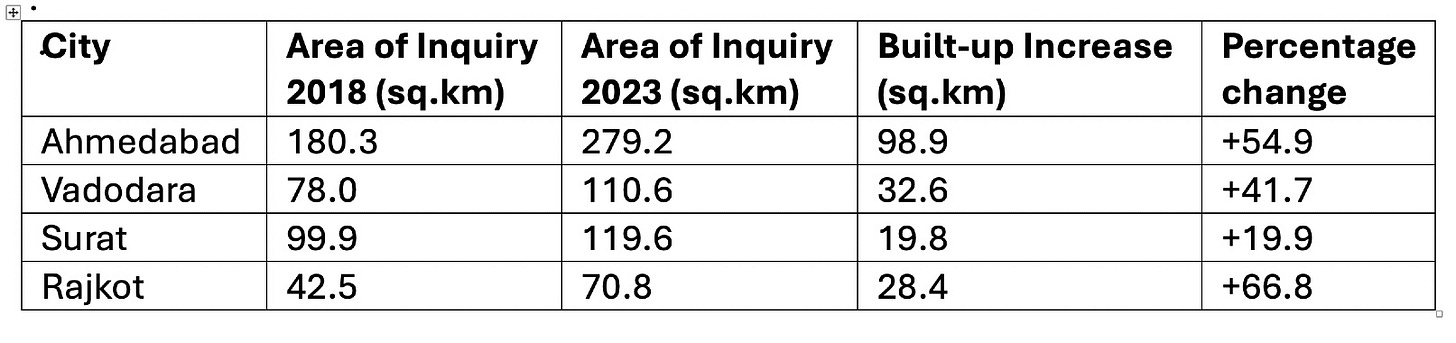

The table below quantifies this peripheral built-up growth between 2018 and 2023:

Ahmedabad witnessed the largest absolute increase in built-up area in the ‘Area of Inquiry’, while Rajkot recorded the highest percentage growth despite starting with the smallest built-up base in 2018. Vadodara also saw substantial growth both in absolute and relative terms. Surat showed comparatively moderate growth.

This analysis highlights rapid peripheral expansion adjacent to the planning boundaries. Key factors driving this growth could be the availability of inexpensive land, limited regulatory oversight, industrial growth, and residents’ preference to move away from core urban areas. Further research is needed to validate these drivers across the four cities.

Urban sprawl is a reality, and its unregulated manifestation is clearly visible in the peripheral belts of Gujarat’s major cities. One way to tackle this challenge is to reduce the incentives for haphazard growth by rationalizing building regulations within the planning jurisdiction. A more calibrated approach to permissible uses, setbacks, FAR (Floor Area Ratio), etc. could help reduce some of the pressure of urban sprawl.

Secondly, a proactive strategy is required for areas beyond the current planning boundaries. Rather than leaving these areas to evolve organically, district authorities could identify future expansion zones and prepare basic layout plans in consultation with the planning authorities for securing adequate Right of Way (ROW) for roads, parks, and the development of trunk infrastructure.

Reading

The Spatial Economy

Author: Suyash Rai

Since they are typically in decision-making positions, the best urban planners and designers possess good practical knowledge (‘know-how’) that is essential for improving the built environment in cities. On the other hand, economic geographers and urban economists build theoretical knowledge (‘know-that’) by developing concepts and models, and identifying patterns in observed facts. Bridging these forms of knowledge can potentially have beneficial spillovers.

For this to happen, it is important for these communities to listen to what the others have to say. This is not easy, because they speak very different languages. Improving the practice of planning and design, and enhancing the usefulness of research in urban economics and economic geography, requires building connections between these domains of knowledge. It also requires movement within each of these fields to find common ground with other fields of knowledge. While planners and designers have always worked with a spatial imagination, it is only in the last three or four decades that economists have started taking space seriously. Many works have contributed to this shift.

Authored by three influential economists – Masahisa Fujita, Paul Krugman, and Anthony Venables – The Spatial Economy is a landmark contribution to economic geography and urban economics, offering a rigorous and elegant theoretical framework for understanding how economic activity is distributed across space. The book synthesised existing knowledge on the theory of economic geography at the time. Since then, the field has flourished, but this book remains a field-defining work. It reviews and synthesises earlier work in ‘new economic geography’ and integrates insights from international trade, urban economics and industrial organisation.

It offers a deep, structured exploration of how economic forces and spatial arrangements interact. Its central argument is that spatial economic outcomes – such as the growth of cities, regional disparities and trade patterns – are not simply exogenous or historically determined, but are shaped by fundamental economic forces related to scale economies, transport costs, and the mobility of goods, people and capital.

While it is written by economists for a primarily academic audience, its core ideas are highly relevant for urban planners and designers – especially those interested in the spatial logic of urban growth, regional inequality, and the impact of infrastructure and trade on cities. At its heart, the book asks: Why do cities form where they do? What forces determine the shape and size of cities? How do infrastructure, trade and agglomeration interact to shape urban and regional landscapes? Although the answers are expressed in mathematical models, the concepts they reveal are intuitive, powerful, and directly relevant to the practice of urban planning and design.

It is theoretical in nature, heavily model-driven, but quite valuable for planners who seek a deeper understanding of the invisible forces that shape urban form. Here are some key insights from the book.

1. Agglomeration is at the heart of cities

At the core of The Spatial Economy is the concept of agglomeration economies – the idea that firms and people benefit from being close to one another. The book mathematically formalises why and how centripetal forces (such as market size effects, knowledge spillovers and shared infrastructure) pull economic activity together, while centrifugal forces (such as congestion, high rents and immobile resources) push it apart.

Understanding the natural pull of agglomeration helps planners respect and harness clustering dynamics, rather than resist them. Efforts to ‘spread out’ activity artificially, without acknowledging these underlying economic logics, are likely to fail or generate inefficiencies.

2. Trade costs shape urban and regional form

One of the book’s major contributions is showing how even small reductions in transport or communication costs can dramatically reshape spatial economies. Trade costs don't just affect international trade – they deeply influence where firms locate and where cities emerge.

Investments in infrastructure (such as highways, ports, or fibre-optic cables) are not neutral: they are powerful tools of spatial reorganisation. Urban designers should carefully consider how changes in infrastructure can shift the balance between agglomeration and dispersion.

3. Historical accidents can lock in urban patterns

The models show that once a city forms, it can maintain its economic advantage through self-reinforcing mechanisms (such as larger labour markets, deeper supplier networks and better amenities), even if initial reasons for its location (such as proximity to a river or a resource) no longer matter.

Urban form often reflects path dependence. While planners may dream of building entirely new cities from scratch, The Spatial Economy reminds us that existing cities possess durable advantages that need to be worked with, not ignored. Redeveloping struggling areas or building new towns requires more than just good design – it needs interventions that can compete with the gravitational pull of existing centres.

4. Multiple equilibria and the role of policy

The models demonstrate that economies can end up exhibiting very different spatial patterns depending on small differences in initial conditions or policy interventions. Some cities may grow large while others stagnate, not because of inherent superiority, but because of early advantages that are amplified over time.

Urban policies – especially those that target early-stage infrastructure, skill development or innovation ecosystems – can tip the balance in favour of growth. Thoughtful, strategic intervention matters enormously in shaping the future of cities.

5. Core-periphery dynamics

The book introduces the idea of a core-periphery structure, where a ‘core’ of high-income, high-productivity regions coexists with a ‘periphery’ of less-developed areas. As transport costs fall, the periphery may benefit (through improved access) or become hollowed out (as people and firms gravitate towards the core).

Planners and designers working in secondary cities or rural areas must recognise the risks of peripherality. Investments must either create strong local agglomerations or strengthen linkages to the core without simply draining talent and firms away.

The Spatial Economy doesn’t offer simple blueprints for building better cities. Instead, it provides a powerful, model-driven understanding of why cities behave the way they do. Urban design often focuses on the visible – streetscapes, zoning, buildings. But books like The Spatial Economy address the invisible forces – trade-offs in firm location, economies of scale, labour market pooling – that shape how and where cities grow, thrive or decline.

Understanding these forces helps planners move beyond surface-level interventions and think about deeper strategic choices:

Where should new transport lines be placed to strengthen, rather than weaken, local economies?

How can design enhance the benefits of agglomeration (e.g. by making dense areas liveable and attractive)?

When is it worth trying to create a new ‘node’ of economic activity, and when is it better to strengthen existing ones?

Perhaps the most important lesson for planners and policy makers is that urban planning is not about coming up with a vision and imposing it on a city or on a site for a new city. Economic forces do not take cognisance of visions, however aesthetically, socially, economically or ecologically attractive those visions are. Neither can they be conjured out of thin air. A more humble approach that is more respectful of economic forces and attempts to boldly work with them is more likely to succeed.

In short, The Spatial Economy gives urban planners and designers the economic grammar of city formation – an essential complement to the visual and regulatory languages they already use. While later work has built on it, the book remains a classic of the field and is well worth reading. However, The Spatial Economy is not an easy read – it requires some patience and a tolerance for equations – but the insights it offers are profound and valuable. For those designing the cities of tomorrow, understanding the forces described in this book is necessary.