#3: Urban Planning System | Floorspace and Ground Cover | Triumph of the City

An essay on reimagining the urban planning system, an insight on the relationship between urban form, floorspace and plot cover, and a book recommendation on how cities can drive progress.

Essay

Reforming the Urban Planning System

Authors: Bimal Patel and Suyash Rai

In the first issue of this newsletter, we made a case for reimagining urban planning as a public policy discipline. In the second issue, we discussed the kinds of knowledge that urban planners need to be able to make the right decisions. We also suggested that such knowledge cannot be created by urban planners working in isolation. To be able to do this, and to be effective at solving urban built environments problems, planners have to be situated in a broader urban planning system. This system has to be made up of various stakeholders who complement one another and act as checks against each other’s excesses. The most important of these stakeholders are government departments and authorities, professional organisations, private sector firms, academic institutions, and civic associations. Reforming urban planning in India will require reimagining and reforming the urban planning system in which planners work.

Government departments and authorities

If urban planners are to be effective, government has to provide appropriate institutional positions and roles for planers within government. Planners also have to be given the freedom to exercise their professional judgement and be held accountable for their decisions. In India, all three need reforming.

Appropriate institutional positions and roles: Urban planners have to play a coordinating and integrative function within local governments and development authorities. Their plans have to comprehensively bring together the plans and projects of all departments that affect the built environment. They also have to support the identification of current and emerging problems pertaining to urban built environments and work on the formulation of policies and strategies to solve them. All of these are high level functions.

If urban planners are to discharge these functions effectively they have to be appropriately situated within local governments and authorities. They have to enjoy statutory positions, work closely with top level functionaries and be effectively involved in decision making. This means that urban planning has to be at the centre of the municipal functioning. Planners have to be able to engage with political and administrative functionaries, communicate with various civil society stakeholders, ensure coordination with other government departments, make sure that statutory processes and protocols are adhered to, and procure the best urban planning expertise from within or outside government. At present, in most cities, planners do not play such a coordinating and problem-solving role.

Space to exercise professional judgement: Planning involves the exercise of political authority to ensure long-term public interest. It should not be driven by short-term political exigencies. At the same time, planning is not a technocratic activity that can afford to ignore political realities. This is particularly so in democracies. Maintaining a balance where planners are both shielded from and accountable to political authorities is a difficult challenge for both political functionaries and planners. Political functionaries must appreciate the importance of long-term urban planning, and planners must allow space for political functionaries to manage political exigencies. This balance needs to be achieved by formal mechanisms and informal norms that enable a reasonable level of independence for planners, while allowing the political leadership to define the overall objectives and the priorities that the planners pursue.

Governments must enable a secure space for planners to exercise their professional judgement. Planning problems are not all identical and cannot all be solved by taking a rigid, rule-bound approach. Often, on account of locational or other contingent specificities, they are unique. Solving them requires making risky judgement calls, and planners must be able to do this without fear of being penalised for errors of judgement.

Transparency and accountability for planning decisions: A secure space for making independent professional judgements can also be abused, and preventing such abuse is also a difficult challenge. It can be tackled in part by exposing decisions, along with the reasoning underpinning them, to public scrutiny and comment. This is one way to protect the exercise of judgement from abuse.

The government must also hold planners accountable for the efficacy of planning. To do this, planners and governments must come up with indicators of success, and the government must institutionalise monitoring mechanisms that planners have to take into cognisance. This is particularly necessary because towns and cities continuously evolve, and it is therefore necessary for plans and policies to evolve in response. Without such an arrangement, it is easy for urban planning to ossify and become ineffective.

Professional organisations

As is the case with all other professions, planners cannot thrive without a professional identity and a community of peers with whom they share some common values and whose abilities they recognise and appreciate. The profession also needs to be formally organised. It must be able to protect its identity, establish and enforce a code of conduct, ensure continuing education, and promote the pursuit of excellence by recognising and rewarding outstanding professional achievements.

Due to the varied forms of knowledge that must go into planning decisions, other planners, especially those familiar with the context of the decisions, are well-placed to make an assessment about the quality and ethics of a planning decision. The formal checks and balances discussed previously in this essay are not sufficient. Planners must also be driven by a professional ethic that disavows the abuse of a professional privilege. Such an ethic is enforced by the personal commitment of a planner, peer pressure from fellow urban planners, and exemplified by the lives of the best urban planners.

Urban planners often work in a political economy context with strong political and economic incentives to put pressure on them to take decisions that benefit specific stakeholders at the cost of the larger public interest. Resisting such pressures is partly about the way individual professionals cultivate values that help them take the right decisions despite undue pressures. However, it is difficult to resist such pressures unless the professionals feel well-supported by their own peers in the profession. Well-organized professional associations can help individual professionals navigate such challenges by standing with those who are taking the right decisions. Such an association should be able to achieve cooperation and collective action among the professionals to serve the larger purpose of planning as a profession.

From regulating entry into the profession, to the continuing education of professionals, to giving support to young professionals, to holding professionals accountable for conduct consistent with the ethical norms of the profession, to working as a platform for collective action and cooperation among the professionals, at their best the professional organisations help strengthen the profession to ensure that it serves the society well. On the other hand, like all associations, professional associations can also become self-serving at the cost of society. It is therefore important to ensure that the professional associations develop well, and it is mainly up to the professionals to do so.

Private sector firms

Given that urban planning is a statutory activity, government planning departments serve a core function in its practice. However, they are not sufficient by themselves and cannot bear the burden of urban planning alone. This is not merely because of logistical reasons but because the task is much too vast for government staff alone to accomplish. In addition to this, there are two other reasons why government departments are insufficient for building urban planning capacity.

First, urban planning, besides requiring the use of statutory authority, also requires creative problem-solving and coming up with previously unthought-of planning approaches and policies. Out-of-the-box creative thinking requires a liberal, non-hierarchical institutional setting and an institutional culture where criticism and openness are encouraged. Government departments are designed for the exercise of statutory authority. Their cultures are typically hierarchical and rule-bound, and therefore government departments are not the best sites for such creative thinking. This is why, if planning is to be effective, the actual work of coming up with plans and policies must be distributed between government departments and professional firms in the private sector.

Second, professional firms in the private sector, unlike government planning departments, are not tied to one city or state. They have to work across cities and states, which gives them exposure to a wider variety of problems and contexts, thus creating the opportunity to acquire more diverse learnings and insights. This experience allows firms to build more robust problem-solving capacities and come up with solutions at a faster pace.

Both of the foregoing reasons for distributing urban planning work between government and private sector firms are well recognised in many other sectors, such as architecture, engineering and construction. Architects and engineers in government departments play a managerial role and collaborate with their counterparts in private sector firms to solve commonly occurring problems.

Professional planning firms, if they are to play their part in the planning system, must maintain a commitment to professional values, technical competence and professional excellence. They must also maintain a commitment to supporting the government in the work of urban planning. Ensuring that they maintain such a stance requires the government to adopt a procurement policy that promotes healthy competition between firms and rewards depth of professional expertise and excellence.

In addition to professional planning firms, real estate firms can also play an important role in providing practical inputs on plans. They are among the most important users of the plan, creating the built environment within the stipulated constraints. Their experience can be valuable in assessing whether a particular plan is likely to work well. Since these firms have high-powered incentives to shape the plan to serve their narrow self-interest, it is up to the planning system to take inputs from firms and put them to use in public interest.

Academic institutions

Academic institutions have multiple roles to play.

Teaching and training: They must train competent and creative urban planning apprentices who, after a period of apprenticeship, can become professional urban planners. Apprentices must be trained to use insights from public policy disciplines along with their technical knowledge to solve planning problems. They also have to understand current practice, appreciate the history of planning and get a sense of what the profession is about.

Research and policy analysis: Academic institutions should also support the profession through research and policy analysis. They must help clarify planning philosophy and theory, excavate and interpret the history of planning, critically appraise practice, and bring the best available knowledge from diverse academic disciplines to enrich thinking in urban planning. This knowledge creation function is crucial to a well-functioning planning system. It provides a key underpinning of good planning, as it ensures that planning is informed by relevant knowledge.

Public interest critiques of plans and regulations: Academic institutions can also play a role in critiquing the draft plans and giving inputs on them. In other domains, when draft regulations and policies are placed in the public domain, some of the most trenchant critiques tend to come from academic institutions that are deeply invested in the study of that domain. The same should be the case with the planning process. This requires academic institutions to develop a deep, historically rooted understanding of specific cities. The more such institutions develop in various cities, the better it would be for the planning system.

Civic associations

Citizens’ groups and city-based non-governmental organisations can play an important role in shaping the built environment of a city. Since they operate in a space that is neither commercial nor state-led, they can bring different perspectives and knowledge to the planning process. Many of them are focused on specific issues, such as environmental protection, access for the disabled, improving public health, and so on. A few are invested more broadly in the overall improvement of the city.

As with the participation of private sector firms, to fully benefit from the participation of civic associations, it is crucial for the urban planning process to be participatory and inclusive. Being participatory implies being open and transparent during the course of the planning process rather than simply releasing a plan as a fait accompli. Being inclusive means making efforts to seek inputs from a variety of stakeholders, including civic associations, and reducing the cost of participation in the planning process. For instance, many civic associations may not be familiar with the technical language of planning but may still be able to express important concerns for planners to consider. Taking inputs from these associations, responding to them and incorporating them into the planning process is the responsibility of the planners.

Urban planning legislations

Urban planning needs a legal mandate. Planning legislations are therefore fundamental to the institutional framework in which planners work. At a minimum, they allow the government to define planning jurisdiction, constitute planning and infrastructure development authorities, define the scope of planning, mandate authorities to formulate plans and frame regulations, mandate all development to comply with plans and regulations, allow authorities to appropriate land, and levy charges to defray the cost of planning and infrastructure development.

The planning legislations set the context for the planners to do their work. The powers, procedures and accountability mechanisms are built into these legislations. Reimagination and reform of the urban planning system will require review and reform of these legislations. In the interim, some of the principles of the urban planning system could be introduced through administrative decisions, but such an approach soon runs into serious limitations because government agencies are mainly creatures of the law, or at least they should be. When it comes to transparency and accountability mechanisms, planning authorities are likely to do no more than what the law expects. Similarly, other stakeholders, especially political and administrative leaders, are not likely to give them more independence than what is enshrined in the law. The interactions between planners and other stakeholders, whether in terms of taking inputs, sharing information, seeking feedback, procuring services, etc, should be envisaged by the planning legislations.

Conclusion

If planning is only focused on creating new cities and developing new areas, the role of the urban planning system is more limited than the one described in this essay. To be truly useful for building better cities, planning must address the current and emerging problems in existing cities. Such a role cannot be performed well unless planners work as a part of a broader urban planning system, along with government departments and agencies, professional associations, private sector firms, academic institutions, and civic associations. This requires a change in the procedures and mechanisms used by planners and a shift in the norms around the planning process to make it more open and inclusive. Among other things, these changes require reform of the planning legislations that both enable and constrain the way the planners work.

Reform of urban planning in India needs to be pursued at two levels. First, we need to reimagine the ideas that underpin the practice of urban planning. Among other things, doing so needs a redefinition of planning as public policy, which includes some regulatory and some development functions. Second, we need to rebuild the urban planning system towards the creation and use of the knowledge that makes better urban planning possible, enables the exercise of sound professional judgement in planning decisions, and enforces proportionate accountability for planning decisions. The role of urban planners should be imagined as that of coordinators and decision-makers within this system. Only if the system works well can planners do their job well.

Insight

Floorspace, Plot Coverage and Number of Floors

Authors: Bimal Patel and Shweta Modi

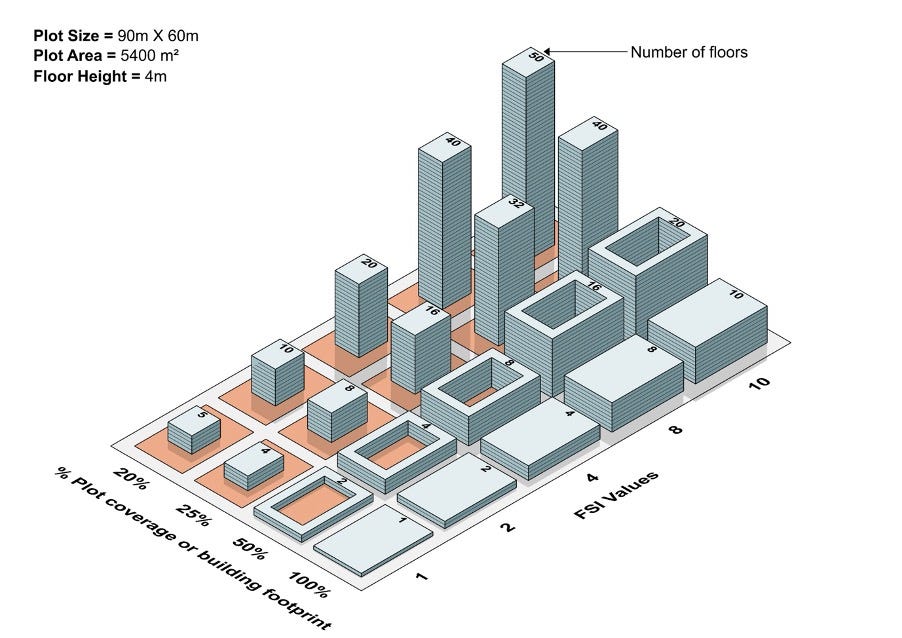

The above diagram takes a hypothetical plot measuring 90m by 60m (5400 sq. m.) and shows various ways in which it can be built upon. It is meant to illustrate the relationship between the amount of floor space, the proportion of plot covered by building (plot coverage) and number of floors. All the plots in the columns have the same amount of building cover. The buildings in each of the rows have the same amount of floorspace. In the first row all the plots have buildings with as much floorspace as the plot area and therefore their floor space indices (total floor space/plot area) are all the same – 1. However, because of their varying plot coverages, the number of floors that those buildings have varies from 1 to 5. In the last row the total floor space in all the buildings is ten times the plot area and the number of floors varies from 10 to 50. This diagram, clarifies two important issues.

First, it is not necessary to build tall buildings to accommodate more floor space. More floor space can also be accommodated by increasing plot coverage. As shown above, doubling plot coverage from 25 percent to 50 percent reduces the number of floors that have to be built by half. This is very important to keep in mind because, generally speaking, beyond 4 floors, building more floors is exponentially costlier. Building regulations that force low plot coverages impose high costs on plot owners. Additionally, buildings that do not rise above tree tops can also be better shaded, making them more energy efficient. Building regulations that force people to build tall also do not make sense from an environmental point of view.

The second important issue that this diagram illustrates is the value of leaving open space in the middle of plots instead of on their peripheries. Building on the perimeter of plots instead of in the middle of plots yields a consolidate and shaded open space in the middle. Such a courtyard space can be put to far better use than strips of land on the periphery. Building on the periphery also allows higher levels of plot coverage and the increased length of facades can improve light and ventilation within buildings. Modern Indian building regulation force people to leave space around buildings. In contrast, all traditional Indian settlements were made up of buildings with courtyards in the middle of buildings.

Reading

Cities Drive Progress

Author: Suyash Rai

Economist Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City is a compelling, data-driven argument in favour of urbanisation. Blending history, economics, and policy analysis, Glaeser offers fresh insights into why cities thrive or decline, with examples from New York and London to Mumbai and São Paulo. He contends that cities are humanity’s greatest invention - engines of innovation, economic growth, and social progress. The future of developing countries, especially India and China, depends on how they urbanize. This book offers valuable ideas for navigating that complex process. Here are five key insights particularly relevant for developing countries:

1) Cities as Engines of Growth

Glaeser shows the powerful link between urban density and innovation. Proximity enables the exchange of ideas, making cities fertile ground for entrepreneurship and technological advancement. Dense areas tend to have stronger economies, higher incomes, and greater upward mobility. Taking Bangalore as an example, Glaeser shows how dense networks of skilled, entrepreneurial individuals connected to global markets create wealth through idea exchange. Unlike typical urban planning books focused on zoning or design, Triumph of the City is rooted in economics, showing how density fosters learning, productivity, and creativity: “Ideas move from person to person within dense urban spaces, and this exchange occasionally creates miracles of human creativity.”

However, this is not automatic. Successful cities emerge through varying models: imperial cities like Tokyo that win through scale, well-governed cities like Singapore, knowledge hubs like Boston, lifestyle cities like Vancouver, and fast-growing cities like Atlanta. What matters most is building better people - through education, skills, and entrepreneurship - more than just structures. Flexibility, good governance, and human capital are the real drivers of urban success. Glaeser challenges conventional wisdom by advocating for policies that ease building restrictions, strengthen public services, and support human development rather than simply expanding infrastructure.

2) Lessons from Declining Industrial Cities

Glaeser’s analysis of industrial decline offers stark lessons for developing countries. Using Detroit and the broader Rust Belt as examples, he shows how cities falter when they lose their capacity to reinvent themselves, becoming overly dependent on a single industry. Detroit, once a hub of inventors, became trapped by Ford’s assembly-line model - prioritising physical scale over human capital. Political missteps worsened the decline, as leaders alienated middle-class residents and focused on consolidating power. Instead of investing in people, cities doubled down on large projects like stadiums and light rail - what Glaeser dubs the “Edifice Complex.”

The underlying lesson is that struggling cities suffer from excess infrastructure relative to their economic strength. Investing more in physical structures rarely solves the problem. In contrast, New York adapted by pivoting to finance and knowledge-based industries, showing that reinvention is possible. Ultimately, cities die when they lose diversity, entrepreneurship, and the human capital necessary for adaptation.

3) Poverty and Inequality in Cities

While broadly optimistic about urbanisation, Glaeser acknowledges the challenges cities face - congestion, pollution, disease, and inequality. Poorly planned urbanisation, especially in developing countries, leads to slums and inadequate services. But Glaeser argues the solution is not to slow urban growth but to make cities more liveable and inclusive. He advocates vertical expansion, better governance, and investments in education over costly infrastructure projects.

Cities, he insists, do not create poverty - they attract the poor seeking better lives. Urban poverty is often preferable to rural destitution because cities offer opportunities for upward mobility. The key question is whether cities enable that mobility or merely serve as refuges from rural hardship. He criticises misguided urban renewal efforts that isolate the poor and worsen conditions. Slums, Glaeser argues, are often productive spaces representing people’s desire for opportunity. Instead of demolishing slums, governments should invest in the people who live there.

4) Overcoming the Challenges of Urbanisation

Glaeser also details how Western cities overcame the downsides of density - disease, pollution, and crime. The turning point was massive investments in clean water, sewage, garbage collection, and policing. Examples like New York’s Croton Aqueduct and Chicago’s sewer systems illustrate how such improvements transformed urban life. Cities became safer not because people improved but because governance and services did. Simple steps like street cleaning dramatically increased life expectancy. Successful cities, Glaeser argues, invest in health, safety, and infrastructure to manage the costs of density.

5) In Defence of Skyscrapers

Glaeser counters the opposition to skyscrapers, arguing they can help improve prosperity, affordability, and environmental efficiency. Vertical growth allows cities to maximise land use and improve housing affordability. Yet restrictive zoning, preservation policies, and height limits stifle growth, worsening affordability in places like New York, Paris, and Mumbai. Aesthetic opposition to tall buildings leads to bad policy - Paris preserved its past but pushed out the poor; Mumbai’s height limits created sprawl, slums, and corruption.

He also challenges suburban environmentalism, arguing that dense cities are greener than suburbs. Cities like New York use less energy due to shorter commutes and smaller homes. Restricting urban growth pushes development to car-dependent suburbs, increasing emissions. Smart environmentalism means building up - supporting dense cities rather than forcing sprawl.

Overall, Triumph of the City is an insightful, engaging, and well-researched book essential for policymakers, urban planners, economists, and anyone interested in the future of cities. Glaeser’s writing is accessible yet rigorous, blending academic analysis with compelling storytelling. His arguments challenge common misconceptions about urbanisation, making a persuasive case for embracing cities rather than fearing them. For those interested in urban economics and policy, this book offers a valuable framework for understanding why cities succeed or fail - and how they can improve human welfare. It is highly recommended for anyone seeking to appreciate the economic, social, and intellectual vitality cities bring to modern life.

Why are tall buildings bad for the environment? My understanding of the current state-of-the-art in urbanism is that it is best to build tall buildings having a high density of people so that each unit of infrastructure serves the maximum amount of people.

Tall buildings might be objectively worse in terms of economic impact, but I'd argue that they limit city sprawl. Sprawling cities are the worst environmental disaster conceived by mankind but they're necessary for humanity's survival. So might as well build tall and minimize the city's impact.