#1: Welcome | Reimagining Urban Planning | Poor Usage of Land | London and the Spirit of Progress

An essay calling for first principles thinking in urban planning in India, an insight on wastage of land in Indian cities, and a book recommendation on a pivotal period in London's history.

Welcome to the first issue of Ideas for Indian Cities, a newsletter of the CEPT Urban Planning and Design Foundation (CUPDF), a Centre of Excellence for research and capacity building under CEPT University. This newsletter will present ideas, explanations and interpretations to help improve the built environment in Indian cities and thereby improve life in these cities. Each issue will include an essay, an insight, and a reading recommendation.

Essay

Reimagining Urban Planning in India

Authors: Bimal Patel and Suyash Rai

Cities are dense and complex agglomerations of vast numbers of people living, working and interacting in close proximity. Their built environments are made up of buildings, open spaces and infrastructure. Cities also have a substantial impact on the quality of life and productivity of the people living in them. Developing well-functioning built environments presents a highly complex problem for two reasons. First, they have to meet the highly specific and continuously evolving needs, preferences and budgets of individuals, families, firms, clubs, shopkeepers, restaurateurs, industrialists and a myriad other such actors that make up towns and cities. Second, buildings, open spaces and infrastructure elements are established by a large number of uncoordinated and diversely motivated actors such as developers, government agencies, utility companies, private firms, households, individuals and many others. Such environments are also built over long periods of time. Yet, they have to complement one another and work in a fairly unified manner.

The need for both markets and government intervention

Building well-functioning cities requires a balance between markets and government intervention. Markets are necessary to reveal – through the price system – demand for space, utilities and transport, and to meet that demand through suitable supply responses. We use the term ‘market’ here in a broad sense – it includes all non-government mechanisms for cooperation and collective action, including community-based institutions that may emerge to shape the built environment.

Markets in cities are driven by the needs of individuals, families, firms, communities and other actors. These actors seek to meet their requirements in terms of location, quality and quantity while staying within their budgets. Supply is organised by profit-seeking builders, developers and service providers. This market system generally ensures that people get what they want at a price they are willing to pay. Markets also allocate resources like land and space and provide price signals that guide production.

However, markets alone are not sufficient because they are prone to failures that can lead to inefficient outcomes. Unmitigated market interplay can lead to several problems in the built environment:

· Inadequate public amenities: Markets may fail to provide sufficient public spaces like streets and parks, as individuals are unlikely to pay for common facilities. Public amenities that are free to access are also likely to be undersupplied because no one has the incentive to supply them.

· Neglect of common spaces and resources: Resources like playgrounds and lakes may be abused and spoilt due to a lack of upkeep. These costs are borne by everyone or at least the part of the city in proximity to these spaces and resources.

· Undersupply of infrastructure: Competition, or simply the lack of rights of ways, can undermine the provision of essential services like water, sewerage and transport systems.

· Congestion and overcrowding: Businesses and households vying for close proximity can lead to excessively congested marketplaces, office districts and residential areas.

· Imposition of externalities: In cases where people allow nuisances generated by them, such as smoke and noise, to spill over onto neighbours, their environments are bound to be polluted.

· Poor quality of the built environment: Unscrupulous developers may cut corners, and consumers may lack the information to assess building quality.

· Unacceptable inequities: Richer residents may create enclaves or capture all the best common resources a city has to offer, leaving those with fewer resources facing unaffordable prices, unmet needs and an unacceptably iniquitous experience of the city.

Unregulated market operations can thus result in uncomfortable, unsafe, inefficient, unequal and unattractive cities, depriving residents of a flourishing life. Government interventions are necessary to regulate markets and, when needed, to provide services. The main form that this intervention takes vis-à-vis the built environment is urban planning.

The importance of urban planning

The failure of unfettered markets necessitates government intervention and collective action. Urban planning can help achieve outcomes that markets on their own may not produce. By focusing on problems that markets are not expected to solve, urban planning can make many people better off without making anyone worse off.

Urban planning can be understood as the government intervention to coordinate, regulate and support the production of urban built environments. It uses government authority to regulate urban growth, ensuring that cities are comfortable, safe, efficient, equitable and beautiful. Without urban planning, societies cannot have good cities that support flourishing lives and expanding economies.

Urban planning entails making plans that everyone abides by; appropriating land for common amenities like streets, parks and utilities; providing information to inform building decisions; making and enforcing regulations of the built environment that keep people from harming one another; ensuring the construction of well-designed and well-built structures; protecting vulnerable areas; preserving sensitive environments; and enabling the provision of water supply, sewerage, storm water drainage, transport systems and other essential services.

The challenges of urban planning

Urban planning is a difficult public policy challenge prone to failure. Planners can easily mistake ‘planning’ for ‘design’. Believing this, they can make urban plans that are akin to architectural plans for company towns like Jamshedpur, or new towns like Chandigarh, where everything can and has to be designed. When planning for real cities, very few elements can and need be designed. Planners can also mistakenly believe that they know what people need, that they can predict their future requirements and that they can produce better outcomes than markets. This can lead them to downplay the important role of markets in city building. Planners can also ignore politics and fairness and overestimate the government’s ability to implement plans.

The many specific ways in which plans and regulations can fail include:

· Excessive central planning: In their bid to segregate nuisance-generating activities, planners can restrict people’s location decisions in a way that prevents them from meeting their location preference altogether. This is an example of the costs of intervention outweighing its benefits.

· Capture by interest groups: Since planning is underpinned by state power, it is vulnerable to capture by interest groups that seek to control this power for their own interests.

· Myopic political interference: Planners work within certain political and administrative contexts. Sometimes, politicians and bureaucrats have an incentive to pursue short-term fixes that yield visible results in the short run but may lead to problems in the long run. This can be a source of failure in plans and regulations.

· Unrealistic rules and standards: In their zeal to ensure high-quality building construction, planners can set building and construction standards so high that they drive up building costs and make legal floor space unaffordable to those with meagre resources. Such regulations and standards also often require considerable state capability to enforce. In developing countries, such capabilities are typically not available and are difficult to build in the short to medium term, leading to a lack of enforcement. All this can lead people to disregard building regulations and create opportunities for corruption. It can also fuel the growth and expansion of informal settlements.

· Wasteful and excessively complex regulations: Complicated and poorly framed building regulations can thwart the optimisation of building designs, forcing people to waste resources. This too can drive up building costs and encourage non-compliance with building regulations. Planners can also institute complicated and time-consuming regulatory processes that constrict the supply of floor space. This can drive up property prices and fuel unaffordability.

· Neglect of property rights: In their eagerness to serve the public interest, planners can make unfair plans that disregard property rights and distribute costs and benefits unfairly. This in turn can elicit resentment and opposition from those who are unfairly treated, invite undue political interference in planning, lead politicians to overrule planning policies and undermine the legitimacy of planning.

· Rent-seeking: Planners can also abuse their powers to indulge in rent-seeking behaviour. This can undermine the credibility of urban planning and make it difficult to implement plans and enforce regulations.

Like market failures, planning failures can lead to uncomfortable, unsafe, inefficient and unattractive cities. They can be more difficult to address than market failures.

The challenge of balancing markets and planning

The key challenge in building good cities is to make markets and planning work together. Societies must determine what aspects should be left to markets and where government intervention is needed. This balance is essential for both to work well.

In India, the master planning approach was the orthodoxy for several decades after independence. Under such an approach, the goal became to design cities rather than plan them. The prevalent approach embodied an overbearing role for planning vis-à-vis markets, an overestimation of the planners’ capacity to predict the future, a disregard for property rights, an overestimation of state capacities and financial resources, and a lack of concern for fairness. Such an approach made planning dysfunctional. It also resulted in many other corrosive political economy outcomes. Though problems with the master planning approach are now widely recognised, it continues to be the default approach to statutory planning in India.

Urban planning in India should be seen in the broader context of the history of development policy in India. In some other sectors, such as finance and telecommunications, there has been a significant but still contested and fragile redefinition of the roles of the state and the markets. There is a need for a reimagination of these roles in urban planning as well.

Defining an agenda for change

Several elements are needed for cities to work well. We don’t know what all they are. No one does. But a reimagination of urban planning must be one of our priorities. Doing so is a key requirement for India, and all those interested in urban development should contribute to it.

This reimagination should not be about loosening the grip of master planning through ad hoc fiats that give more freedoms to those in the business of building and investing in cities. It should also not be about disregarding plans to rapidly channel infrastructure investments into cities. Such moves, while they may be expedient, only serve to undermine the vital role of urban planning in building well-functioning cities.

This reimagination should also not be about replacing one design approach with another. Take, for example, the practice of replacing single-use land-use zones with an array of mixed-use land-use zones, or replacing flat floor space index regimes with graded regimes around transit hubs. They seem like attempts at replacing a design approach that disregarded markets with a new one that mimics market outcomes.

We need to forge a new, coherent approach to replace master planning. This new approach should recognise a role for markets and create a framework within which planning and markets can both work well. It needs to be a public policy approach to urban planning that seeks to regulate markets in justifiable and meaningful ways. It should allow space for markets to shape cities and harness their power to solve urban problems. It should allow cities to imagine and reimagine themselves, to build problem-solving and resource-generation capacities, and to incrementally improve themselves over long periods of time.

Finally, this reimagination should not entail a top-down replacement of an earlier approach to planning by a reformed approach. It should be about opening the planning system to critique and experimentation as well as collaboration with various stakeholders who have a civic duty and material interest in shaping the city they live in.

More on all this in the subsequent issues of this newsletter.

Insight

Poor Use of Land in Indian Cities

Author: Bimal Patel

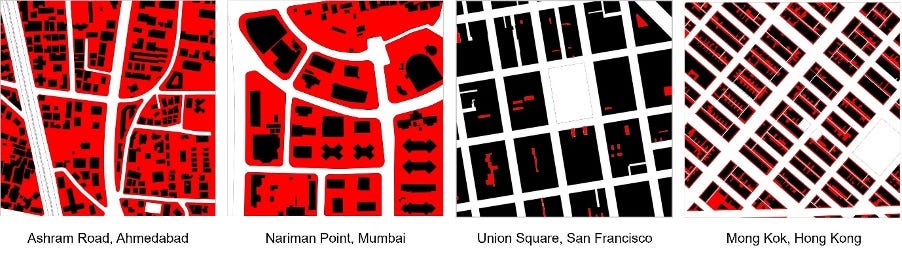

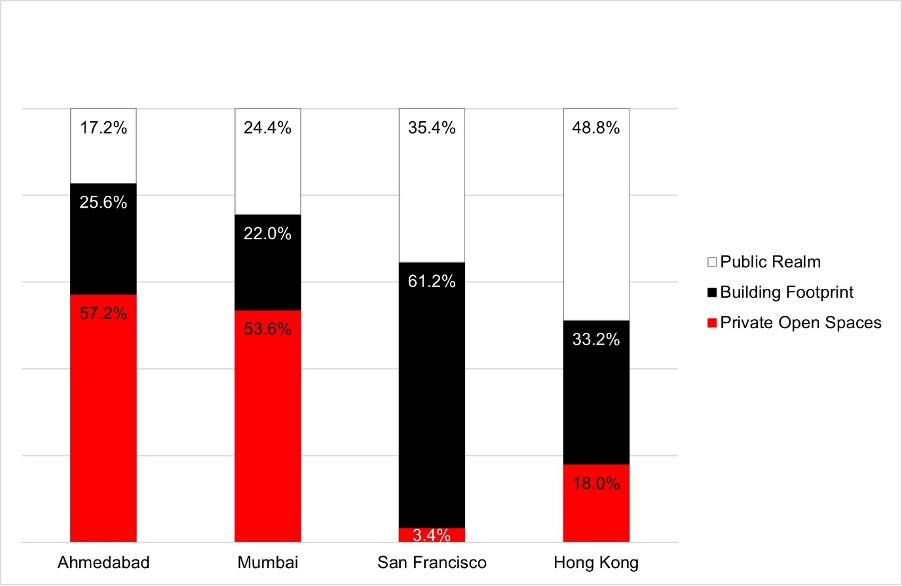

The figures above show 25 hectares in central Ahmedabad, Mumbai, San Francisco and Hong Kong. Land devoted to public streets and parks is shown in white. Land covered by buildings is shown in black. Private open land is shown in red. The below chart presents a statistical comparison of the land use distribution shown in the above visual comparison.

The portions of Ahmedabad and Mumbai shown here, which are characteristic of the rest of the two cities, have a suburban morphology. They are made up of freestanding buildings inside private compounds. This means that a lot of land is devoted to private open space around buildings within compound walls. This land is in the form of thin strips and small irregularly shaped patches, and when it is added up, it constitutes over half the land area. It is left open in this manner because statutory building regulations require it to be so. The remaining half of the land is divided between the public realm and building cover. The former comprises streets and parks, and the latter is the land covered by buildings.

The portions of San Francisco and Hong Kong shown here, which are also fairly characteristic of the rest of their central areas, have an urban morphology. Buildings face the streets directly and cover most of the area available within the private plots. The consequence of this is that much less land is left open behind compound walls. This allows more land to be devoted to the public realm and to buildings. Well over a third of the land is devoted to building streets and parks, and over a half is covered by buildings.

The use of land in Ahmedabad and Mumbai is fairly typical of most Indian cities and is mandated by building regulations. It explains why Indian cities have inadequate street networks and parks and why there just isn’t enough space for all the activities and elements that streets have to accommodate: traffic; pedestrians; trees; bus stops; informal vendors; parking; street furniture; signage; streetlights; light poles; water supply, sewerage and storm water drainage systems; electrical infrastructure; and more. The use of land also explains why Indian cities, despite building tall, are unable to accommodate as much floor space as their well-functioning counterparts in the rest of the world. It also explains why they are spreading out into their peripheries far more than necessary.

Indian building regulations make a default assumption in favour of a suburban morphology. They cause land, which is the only non-expandable element in city building, to be misallocated and poorly used. Correcting this should be an urgent priority for urban planning.

Reading

London and the Making of a Great City

Author: Suyash Rai

For those fascinated by the evolution of great cities, Andrew Saint’s London 1870-1914: A City at its Zenith is essential reading. Chronicling London’s transformation from Dickensian deprivation to a modern metropolis, Saint masterfully interweaves architectural history, urban planning, political economy and everyday life. Richly illustrated and elegantly written, the book captures the city’s restless dynamism, its social reforms, aesthetic experiments, institutional improvements and infrastructural advances.

More than a history of buildings, this book is a story of people, institutions and civic ambition. Saint vividly portrays how civil servants, local politicians, business leaders, artists, activists and professionals – particularly architects and urban planners – contributed to a series of seemingly small changes that, over time, produced profound transformation. The book chronicles how a great city emerges from the accumulated efforts of those who inhabit it.

As G K Chesterton observed, ‘Men did not love Rome because she was great. She was great because they had loved her.’ So too with London; this book reveals how one of the world’s greatest cities was shaped at its peak not through top-down directions by a single entity, but rather a shared spirit of progress and civic engagement.